|

COP14

BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY 2018

PLEASE USE OUR A-Z INDEX

TO NAVIGATE THIS SITE

COP14

the fourteenth ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place on 17 - 29 November 2018, in Sharm El-Sheikh,

Egypt.

The access and benefit sharing protocol of the

UN Convention on Biological Diversity is based on bilateral agreements between providers and users of genetic resources. There are, however, many cases where genetic resources are dispersed, and difficult to attribute to only one location. The issue is being discussed at the biennial meeting of the CBD member states, in particular the possibility of a global multilateral benefit-sharing mechanism to address those genetic resources not yet covered by the protocol. A side event yesterday explored the possible conditions and needs for establishing such a mechanism, and called for urgent action.

The 14th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and the third meeting of the Parties to the Nagoya Protocol [pdf] on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization is taking place from 13-29 November in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt.

Article 10 of the Nagoya Protocol asks that the protocol’s members consider the need for and modalities of a global multilateral benefit-sharing mechanism to address cases of transboundary situations, or for which it is not possible to grant or obtain prior informed consent.

Discussion are ongoing at the COP this week to find agreement on a draft decision on the global mechanism. An unofficial paper [pdf

non-paper] was issued by the co-chairs of the contact group seeking to find agreement on a draft decision. The non-paper calls for a study on specific cases as described in Article 10, answering requests by some member states such as

Japan,

Switzerland, and the

European Union countries (IPW, Biodiversity/Genetic Resources/Biotech, 20 November 2018).

According to the side event organisers, the International Law Research Program, Center for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) in Canada, Article 10 is generating increased attention. The article concerns issues such as transboundary resources, but also shared traditional knowledge, and digital sequence information, they said.

Manuel Ruiz Muller, director and principal researcher for the International Affairs and Biodiversity Program, Peruvian Society for Environmental Law, said the idea of a multilateral fund for genetic resources is not new and was already discussed in the late 1970s.

As the CBD was being negotiated in the late 1990s, a few scholars had proposed the idea of creating some kind of international system of benefit-sharing for the use of genetic resources. However the idea of a multilateral system did not catch on, he said, as countries focused on sovereignty.

A question arising from Article 10, he said, is what is meant by “transboundary.”

Article 10 is treated as an exception, as an exceptional situation but looking at the reality, genetic resources are extremely dispersed and disseminated across countries and jurisdictions. Some countries also share the same type of genetic resource, he said.

According to Ruiz, Article 10 does not apply to exceptional situations but is a substantive dimension of the protocol. An international regime should allow for the free flow of resources. It is not an attack on sovereignty, he said, and benefit-sharing would arise if the innovation based on genetic resources is protected by

intellectual property and generates enough revenue. There is a need to reconsider what sovereignty means, he said.

Saving Biodiversity Cannot Wait

Pierre du Plessis, access and benefit-sharing advisor for the African Union, said the first question when discussing needs is the urgency with which sustainable funding is required to work on biodiversity conservation. “There is not a lot of time to save biodiversity,” he said.

He said a CBD High-Level Panel on the Global Assessment of Resources for Implementing the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 found that an estimated US$150 billion a year would be needed to save biodiversity. According to du Plessis, four sectors (functional food, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and biotechnology) are expected to reach US$3 trillion a year by 2020. A five percent share of those earnings would yield US$150 billion, he said, adding, “we could do it if we really wanted to.”

Article 10 was a placeholder for further negotiations, he said, a ‘wiggle room’ to allow for both the adoption of the protocol, and a way forward. However, Article 10 is essential for the full implementation of the protocol, he said.

He noted that some countries do not have prior informed consent or a benefit-sharing system in place, which still allows for misappropriation of resources. He added, in his presentation, that the scope of the Nagoya Protocol needs to be widened to include resources such as digital sequence information, pathogens, marine genetic resources, and to close loopholes undermining the protocol.

There is a need to reaffirm the commons but with differentiated responsibilities, he said. He suggested establishing a global fund, and that grants be made directly to indigenous peoples and local communities to support local conservation and sustainable use.

Du Plessis also said the aim of the global mechanism could be to collect benefits which are not currently covered in bilateral mutually agreed terms. It would not undermine the bilateral system, and could be based on a blended approach, he said.

Digital Sequence Data, Whether In or Out, Needs Inclusion

According to Margo Bagley, senior fellow with CIGI’s International Law Research Program, there are two approaches to terminology. For some, terminology is not critical, in particular for some providers of digital sequence information (DSI). On the other hand, users have a stronger interest in terminology, for legal certainty and possibility of exclusion, she said.

Other possible terms include natural information, genetic information, genetic sequence data, digital sequence data and more, she said.

The danger of a particular terminology, she said, is the fact that technology continues to evolve and a specific terminology may not capture later developments, just as illustrated by the current question to know whether the Nagoya Protocol includes DSI or not.

Those opposed to the inclusion of DSI, mostly users, argue that the scope of the protocol is limited to tangible material, and that restricting access to GR and DSI would inhibit research. Including DSI would create uncertain monetary obligations, and legal uncertainty, such as about patent rights, they say.

According to Bagley’s presentation, if the definition of genetic material or genetic resources includes DSI, then prior informed consent, and mutually agreed terms on benefit-sharing will “dramatically complicate the legal use of DSI…”

If the definition of genetic material in the protocol does not include DSI, benefit-sharing could potentially be handled under the global multilateral benefit-sharing mechanism as described in Article 10.

A bilateral system, such as the one established by the Nagoya Protocol, is not ideal for dealing with DSI utilisation, Bagley said. This is because there is no robust sequence tracking system, there is a wide use of partial sequence combinations by researchers. They often use sequences from vast numbers of diverse organisms, and the same sequence may occur in multiple organisms from different geographic areas.

For example, she said in her presentation, “the synthetic biology production of steviol glocosides in yeast involves the use of genes from ~ 30 different possible species including a mushroom, grapevine, legume, and a fungal plant pathogen.”

She added that the value of a single sequence can be very difficult to quantify and transaction costs could be difficult to imagine if researchers working with thousands of sequences have to try negotiating benefit-sharing for each of them.

According to Bagley, the lack of monetary benefit-sharing contributes to the lack of conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.

According to Chris Lyal of the United Kingdom Natural History Museum, applying prior informed consent and mutual agreed terms to DSI would imply a very large number of transactions.

He noted in his presentation that there was often very low incremental value of a single sequence to the research, and application of prior informed consent and mutually agreed terms on DSI would be detrimental to the use of DSI, and act directly against CBD implementation.

SUBSIDIARY

BODY ON SCIENTIFIC TECHNICAL AND TECHNOLOGICAL ADVICE

The

twenty-first and twenty-second meetings of the SBSTTA took place in Montreal, Canada

between 2 - 7 July 2018 and 11 - 14 December 2017.

PARTIES

TO THE CONVENTION

As of 2016, the

Convention

on Biological Diversification had 196 parties, which includes 195 states and the European

Union. All UN member states - with the exception of the United

States - have ratified the treaty.

The

United Nations is the link between other Conferences of the

Parties to include Climate

Change and Desertification.

It is a bit confusing to have so many different conferences

that deal with interconnected issues. In addition, each member

state will have their own meetings on the subject to decide

what their position will be at the COPs. We wonder then at the

size of the carbon

footprints so generated in relation to the effectiveness

of the decisions - that at the moment do not appear to be

working to stabilize our climate, stop deserts from being

created, or protect the habitats of our species.

In

our view a climate emergency should have been declared, to

accelerate a change from fossil

fuels to clean energy harvesting. Not only to protect

coral and other endangered species, but also to ensure long

term energy

security for the parties.

CONFERENCES

OF THE PARTIES

The convention's governing body is the Conference of the Parties (COP), consisting of all governments (and regional economic integration organizations) that have ratified the treaty. This ultimate authority reviews progress under the Convention, identifies new priorities, and sets work plans for members.

The Conference of the Parties (COP) uses expertise and support from several other bodies that are established by the Convention.

The main organs are:

(a)

review of progress in implementation;

(b) strategic actions to enhance implementation;

(c) strengthening means of implementation; and

(d)

operations of the convention and the Protocols.

National Reports

Parties prepare national reports on the status of implementation of the Convention.

MARINE & COASTAL BIODIVERSITY

The oceans occupy more than 70% of the Earth’s surface and 95% of the biosphere. Life in the sea is roughly 1000 times older than the genus Homo.

There is broad recognition that the seas face unprecedented human-induced threats from industries such as

fishing and transportation, the effects of waste disposal, excess nutrients from

agricultural runoff, and the introduction of exotic species.

If we fail to understand both the vulnerability and resilience of the living sea, the relatively brief history of the

human species will face a tragic destiny.

What's the Problem?

According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, the world’s oceans and coasts are highly threatened and subject to rapid environmental change. Major threats to marine and coastal ecosystems include:

* Land-based pollution and euthrophication

* Overfishing, destructive

fishing, and illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing

* Alterations of physical habitats

* Invasions of exotic species

* Global climate change

CONTACTS

Cristiana Pașca Palmer

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity

413, Saint Jacques Street, suite 800

Montreal QC H2Y 1N9

Canada

Tel: +1 514 288 2220

Fax: +1 514 288 6588

E-Mail: secretariat@cbd.int

Web: www.cbd.int

BIODIVERSITY

COP HISTORY

|

COP

1: 1994 Nassau, Bahamas,

Nov & Dec

|

COP

8: 2006 Curitiba, Brazil, 8

Mar

|

|

COP

2: 1995 Jakarta, Indonesia,

Nov

|

COP

9: 2008 Bonn, Germany,

May

|

|

COP

3: 1996 Buenos Aires, Argentina,

Nov

|

COP

10: 2010 Nagoya, Japan,

Oct

|

|

COP

4: 1998 Bratislava, Slovakia, May

|

COP

11: 2012 Hyderabad, India

|

|

EXCOP:

1999 Cartagena, Colombia, Feb

|

COP

12: 2014 Pyeongchang, Republic of Korea, Oct

|

|

COP

5: 2000 Nairobi, Kenya, May

|

COP

13: 2016 Cancun, Mexico,

2 to 17 Dec

|

|

COP

6: 2002 The Hague, Netherlands,

April

|

COP

14: 2018

Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, 17 to 29 Nov

|

|

COP

7: 2004 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Feb

|

COP

15: 2020 Kunming, Yunnan, China

|

CLIMATE

CHANGE UN COP HISTORY

|

1995

COP 1, BERLIN, GERMANY

1996

COP 2, GENEVA, SWITZERLAND

1997

COP 3, KYOTO, JAPAN

1998

COP 4, BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA

1999

COP 5, BONN, GERMANY

2000:COP

6, THE HAGUE, NETHERLANDS

2001

COP 7, MARRAKECH, MOROCCO

2002

COP 8, NEW DELHI, INDIA

2003

COP 9, MILAN, ITALY

2004

COP 10, BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA

2005

COP 11/CMP 1, MONTREAL, CANADA

2006

COP 12/CMP 2, NAIROBI, KENYA

2007

COP 13/CMP 3, BALI, INDONESIA

|

2008

COP 14/CMP 4, POZNAN, POLAND

2009

COP 15/CMP 5, COPENHAGEN, DENMARK

2010

COP 16/CMP 6, CANCUN, MEXICO

2011

COP 17/CMP 7, DURBAN, SOUTH AFRICA

2012

COP 18/CMP 8, DOHA, QATAR

2013

COP 19/CMP 9, WARSAW, POLAND

2014

COP 20/CMP 10, LIMA, PERU

2015

COP 21/CMP 11, Paris, France

2016

COP 22/CMP 12/CMA 1, Marrakech, Morocco

2017

COP 23/CMP 13/CMA 2, Bonn, Germany

2018

COP 24/CMP 14/CMA 3, Katowice, Poland

2019

COP 25/CMP 15/CMA 4, Santiago, Chile

2020

COP 26/CMP 16/CMA 5, to be announced

|

DESERTIFICATION

COP HISTORY

|

COP

1:

Rome, Italy, 29 Sept to 10 Oct 1997

|

COP

9:

Buenos Aires, Argentina, 21 Sept to 2 Oct 2009

|

|

COP

2:

Dakar, Senegal, 30 Nov to 11 Dec 1998

|

COP

10:

Changwon, South Korea, 10 to 20 Oct 2011

|

|

COP

3:

Recife, Brazil, 15 to 26 Nov 1999

|

COP

11:

Windhoek, Namibia, 16 to 27 Sept 2013

|

|

COP

4:

Bonn, Germany, 11 to 22 Dec 2000

|

COP

12:

Ankara, Turkey, 12 to 23 Oct 2015

|

|

COP

5:

Geneva, Switzerland, 1 to 12 Oct 2001

|

COP

13:

Ordos City, China, 6 to 16 Sept 2017

|

|

COP

6:

Havana, Cuba, 25 August to 5 Sept 2003

|

COP

14:

New Delhi, India, 2 to 13 Sept 2019

|

|

COP

7:

Nairobi, Kenya, 17 to 28 Oct 2005

|

COP

15:

2020

|

|

COP

8:

Madrid, Spain, 3 to 14 Sept 2007

|

COP

16: 2021

|

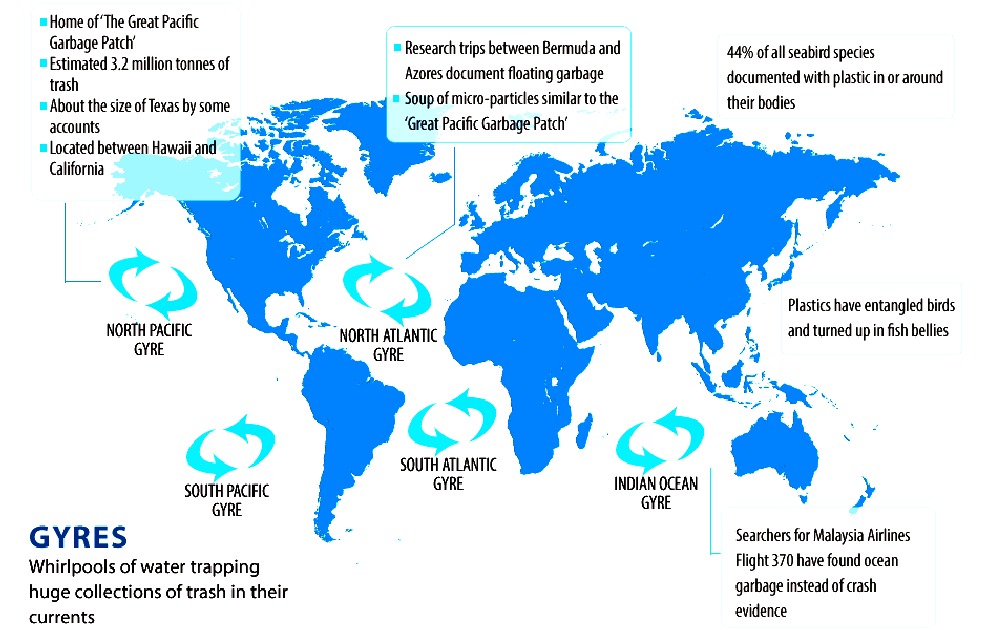

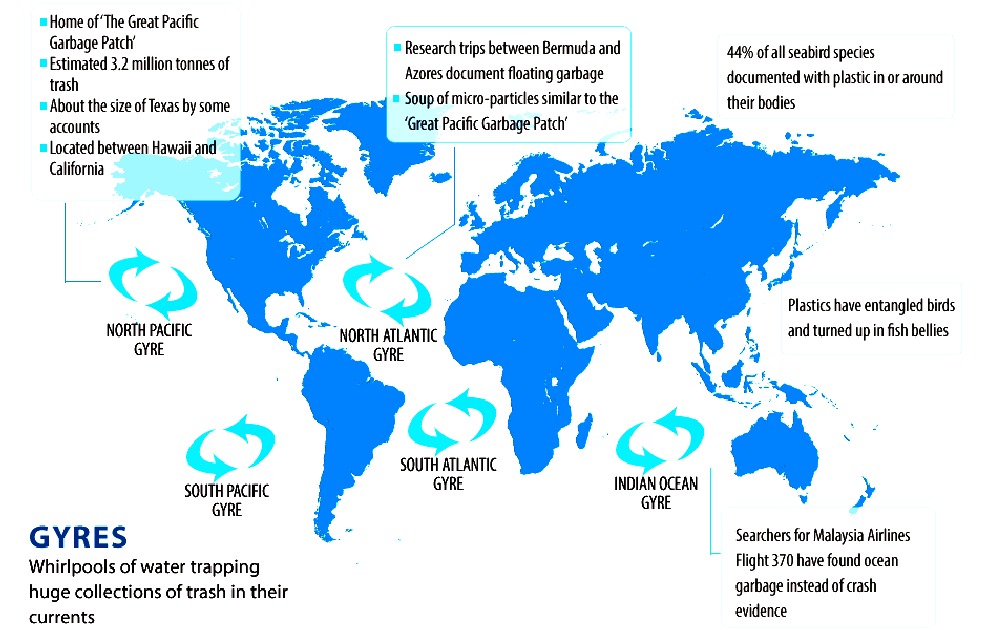

CONSERVATION

RISK

-

Plastic has accumulated in five ocean hot spots called

gyres, see here in this world map derived from information

published by 5 Gyres. The plastic is laden with toxins that

fish and marine mammals mistake for food and eat - eventually killing them.

Marine pollution is thus a major challenge if we are to ensure that species are

not wiped out.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.ip-watch.org/2018/11/27/panellists-cbd-funds-needed-save-biodiversity-genetic-resources-not-nagoya-protocol-included/

http://sdg.iisd.org/events/2020-un-biodiversity-conference/

https://www.cbd.int/meetings/SBSTTA-01

https://worldoceanreview.com/en/wor-1/marine-ecosystem/biodiversity/

https://www.cbd.int/executive-secretary/

https://www.cbd.int/marine/

This website is

provided on a free basis as a public information service. copyright © Cleaner

Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company

No: 4674774) 2019. Solar

Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom.

COFL is

a company without share capital.

|