|

COP10

BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY 2010

PLEASE USE OUR A-Z INDEX

TO NAVIGATE THIS SITE

COP

10 the tenth ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place in in Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture,

Japan, from 18 to 29 October 2010.

Pursuant to decision IX/35, the tenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 10) was

convened

COP 10 included a high-level ministerial segment organized by the host country in consultation with the Secretariat and the Bureau. The high‑level segment took place from 27 to 29 October 2010.

This meeting took place during the International Year for Biodiversity (IYB) as declared by the

United Nations General Assembly through Resolution 61/203. During the course of the year events occured in every region of the world to raise public awareness of the importance of biological diversity to human well-being.

Strategic Issues for Evaluating Progress and Supporting Implementation of the Convention were considered. The Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-sharing was adopted.

One interesting and yet widely unknown angle to this issue is the connection between the endangered brazilwood tree in Brazil’s

rainforest - and the future of classical music as we know it.

This critical problem is explored in depth in the beautifully made documentary film A Arvore da Musica (The Music Tree).

SUBSIDIARY

BODY ON SCIENTIFIC TECHNICAL AND TECHNOLOGICAL ADVICE

The

fourteenth meeting of the SBSTTA took place in

Nairobi, Kenya, 10 - 21 May 2010

THE

GUARDIAN 28 SEPTEMBER 2010 - Putting a price on biodiversity - what are species worth?

At the UN's COP10 biodiversity meeting in Nagoya next month, officials might look to remind the world why species matter to humans: for oxygen, drugs, making

agricultural crops more productive — and a sense of wonder

We live in what is paradoxically a great age of discovery and also of mass extinction. Astonishing new species turn up daily, as new roads and new technologies penetrate formerly remote habitats. And species also vanish forever, at what scientists estimate to be 100 to 1,000 times the normal rate of

extinction.

Over the past few years, as I was working on a book about the history of species discovery, I often found myself coming back to a fundamental question: Why do species matter? That is, why should ordinary people care if scientists discover one species or pronounce the demise of another?

It may seem too obvious to need asking. In certain limited contexts, people clearly do care. We will go to great lengths to protect a boutique species like the giant panda, for instance. We also thrill to the possibility of finding the slightest microbial hint of life in outer space, hardly blinking when the U.S. government spends $7 billion a year largely for that purpose. Meanwhile, we spend pennies exploring the alien life forms that are all around us here on

Earth.

Maybe it's just human nature not to value — or even see — the thing that's right in front of our faces. And maybe it's also a failure of communication.

That is, scientists may need to explain their work on a far more basic level — not "Why do species matter?" but "Is food important to you?" or "Do you want your children to have effective medicines when they get sick?" or even "Do you like to breathe?" None of these questions overstates the importance of species.

For instance, Prochlorococcus is an ocean-dwelling genus of cyanobacteria and among the most abundant life forms on Earth. Why should we care? Because it produces about 20 percent of the oxygen we breathe — and yet until an MIT microbiologist named Sally Chisholm discovered it in 1986, Prochlorococcus was unknown. We need to understand in short that our lives depend on species most of us have never heard of — species we otherwise tend to shrug off as obscure, trivial, even undesirable.

Vultures, for instance. When we cause a species to go into decline, we almost never know — and hardly even stop to think about — what we might be losing in the process. In truth, it may be hard to think about, because the cascading effects of our actions are sometimes freakishly distant from the original cause. So in India in the early 1990s, farmers began using the anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac for the apparently worthy purpose of relieving pain and fever in their livestock. Unfortunately, vultures scavenging on livestock carcasses accumulated large quantities of the drug and promptly died of renal failure. Over a 14-year period, populations of three vulture species plummeted by between 96.8 and 99.9 percent.

Losing these efficient scavengers meant livestock carcasses often got left in the open to rot. It was one of those "ecosystem services" — manufacturing oxygen, soaking up

carbon

dioxide, preventing floods, taking out the garbage — that species generally provide unnoticed, until they stop. But the impacts went well beyond the stench, according to a 2008 article in Ecological Economics. Moving into the niche vacated by the vultures, feral dog populations boomed by up to 9 million animals over the same period. Dog bites and the incidence of rabies in humans also increased, and the authors conservatively estimated that an additional 48,000 people died during the 14-year period as a result. Calculating the bottom-line worth of what we get from the natural world is notoriously difficult. But even pricing lives at a fraction of developed world values, the near-total loss of three insignificant vulture species has so far cost India an estimated $24 billion.

A diversity of species can also help prevent the emergence of new diseases, though we tend to blame, rather than credit, nature for this particular ecosystem service. We sometimes respond to Lyme disease, for instance, by trying to kill the major players, blacklegged ticks and white-footed mice. But the "dilution effect," proposed by Rick Ostfeld at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, suggests counterintuitively that having the broadest variety of host species in a habitat is a better way to limit disease. Some of those hosts will be ineffective, or even dead ends, at transmitting the infectious organism. So they dilute the effect and keep the disease organism from building up and spilling over to humans. But when we reduce biodiversity by breaking up the forest for our backyards, we accidentally favor the most effective host — in this case, the white-footed mouse. And we free the undiluted disease organism to operate at full strength.

The implications go well beyond Lyme disease. Around the world over the past half-century, researchers have tracked about 150 emerging infectious diseases, from Ebola to HIV, with 60 to 70 percent being zoonotic — that is, transmitted from animals to humans. "The question," says Aaron Bernstein, a Harvard pediatrician and co-editor of the 2008 book Sustaining Life: How Human Health Depends on Biodiversity, "is whether humans are doing something to make these zoonotic diseases come out of the woodwork." Clearly, we are doing a lot of one particular thing — knocking down forests and creating species-poor habitats with no "dilution effect" in their place. Thus the fear is that many more such epidemics may lie ahead.

And yet the value of even big, charismatic species remains so poorly understood that a Rutgers University philosopher writing in The New York Times recently proposed gradually wiping out cruel carnivorous species and replacing them with gentle vegetarians. He was upset that lions do not lie down with lambs, except to eat them for dinner. And he was apparently oblivious to the larger cruelty called a trophic cascade: Loss of predators strips a habitat of its diversity and leaves behind the animal equivalent of the civil service, or what writer David Quammen has called "a pestilence of minor nibblers."

For instance, in the rocky world between high and low tides on the Pacific Coast near Seattle, the food chain (or trophic community, from the Greek trophikos, or nourishment) consists of barnacles, limpets, chitins, anemones, and particularly

mussels. Starfish are the dominant predator. So mussels normally crowd up along the high tide line, where starfish are less likely to chomp them. In one study, a biologist removed the starfish to see what would happen. The mussels soon crept down toward deeper water, crowding out other species. Within a few years, only eight of the 15 original species still lived in that neighborhood. For all their apparent cruelty, killer species can be a means of fostering biodiversity.

So do individual species matter? Or is it just the diversity of species? The truth is that our understanding of the natural world is far too primitive for anyone to say one species is important, and another isn't. In fact, scientists don't even have names for most species; they've described only about 1.8 million of them, with an estimated 10 to 50 million still to go. So instead of waging pitched battles for individual species, conservationists in recent years have prudently tended to emphasize diversity, working to protect large swaths of habitat for a multitude of species. It's the motorcycle mechanic's approach to conservation, as articulated by Aldo Leopold: "To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering."

But that should not stop us from trumpeting the benefits to humanity from individual species that might otherwise get written off as worthless, or even as impediments to human progress. Some conservationists may cringe at the thought of cheapening the natural world by defending it in economic terms. But

NASA manages to hold onto a sense of wonder about its mission while simultaneously touting the idea that space exploration can pay for itself in technology transfers to the civilian world. (There's actually a NASA "spinoff coloring book." It celebrates an outer space mirror-polishing technology now also used to make ice skates go "super fast!") The difference is that the spinoff argument for exploring species here on Earth is far more persuasive.

The yew, for instance, was until recently a "trash tree," says David J. Newman of the National Cancer Institute; he figures it was last valued around the time his ancestors used it to fashion bows for firing arrows at the Battle of

Agincourt. But it's now the source for taxol, relied on by tens of thousands of people as a life-saving treatment for breast, prostate, and ovarian

cancers. Sales topped $1.6 billion last year, according to IMS Health, a healthcare information and consulting company. Likewise, no one ever marched to save the gila monsters, but their venom is the source of a new drug for people who resist conventional treatments for Type 2 diabetes, an epidemic disease now on track to affect more than a third of all Americans over their lifetimes.

In fact, the common idea that drug companies can cook up their medicines out of thin air through "rational drug design" in the laboratory is simply wrong. One recent study looked at more than 1,000 drugs approved worldwide over a 20-year period and found not one that was traceable to a totally synthetic source. Getting our ideas from species in the natural world is still the rule.

Likewise, wild species continue to be the mother lode of genetic material for making agricultural crops more productive, or more resistant to pests, disease, and drought. That kind of bio-prospecting is likely to become far more important over the next few years as biologists begin to explore the bacteria, fungi, and other microbial life forms that help plants do what they do.

In fact, we will have little choice but to find smarter ways of exploiting the hidden resources of the natural world. If NASA in its glory years had a mission — to get to the moon in 10 years — biologists now have one, too: To sustain the species and habitat here on Earth that will be essential to providing food, medicine, and sanity as the human population grows to 9 billion people over the next 40 years.

There is one final argument for the value of species, and it has to do with beauty, biophilia, and a sense of the sacred. In the course of researching my book on species discovery, it seemed to me that one young 19th-century specialist in marine mollusks made the case most persuasively. In pursuit of new species along the coast of Alaska, naturalist William T. Dall experienced all the usual adventures, among them a long frigid trip in a sealskin dory across open water, trying to avoid being crushed by waves loaded with cakes of ice.

He gave his family an eloquent explanation of what motivated him, and by extrapolation most other species seekers: "There is a singular delight," he wrote home in 1866, "in taking these delicate and almost microscopic animals and putting them under a strong glass, seeing the tiny heart beat, and blood circulate and gills expand, counting the muscles and blood vessels and almost the tiny disks that form the blood and to know that you are the first that has penetrated these mysteries and are perhaps the only one who ever will, and that all your notes and drawings and observations are so much solid knowledge added to the power and grace and beauty of the Infinite."

by Richard Conniff

PARTIES

TO THE CONVENTION

As of 2016, the

Convention

on Biological Diversification had 196 parties, which includes 195 states and the European

Union. All UN member states - with the exception of the United

States - have ratified the treaty.

The

United Nations is the link between other Conferences of the

Parties to include Climate

Change and Desertification.

It is a bit confusing to have so many different conferences

that deal with interconnected issues. In addition, each member

state will have their own meetings on the subject to decide

what their position will be at the COPs. We wonder then at the

size of the carbon

footprints so generated in relation to the effectiveness

of the decisions - that at the moment do not appear to be

working to stabilize our climate, stop deserts from being

created, or protect the habitats of our species.

In

our view a climate emergency should have been declared, to

accelerate a change from fossil

fuels to clean energy harvesting. Not only to protect

coral and other endangered species, but also to ensure long

term energy

security for the parties.

CONFERENCES

OF THE PARTIES

The convention's governing body is the Conference of the Parties (COP), consisting of all governments (and regional economic integration organizations) that have ratified the treaty. This ultimate authority reviews progress under the Convention, identifies new priorities, and sets work plans for members.

The Conference of the Parties (COP) uses expertise and support from several other bodies that are established by the Convention.

The main organs are:

(a)

review of progress in implementation;

(b) strategic actions to enhance implementation;

(c) strengthening means of implementation; and

(d)

operations of the convention and the Protocols.

National Reports

Parties prepare national reports on the status of implementation of the Convention.

MARINE & COASTAL BIODIVERSITY

The oceans occupy more than 70% of the Earth’s surface and 95% of the biosphere.

Life in the sea is roughly 1000 times older than the genus Homo.

There is broad recognition that the seas face unprecedented human-induced threats from industries such as

fishing and transportation, the effects of waste disposal, excess nutrients from

agricultural runoff, and the introduction of exotic species.

If we fail to understand both the vulnerability and resilience of the living sea, the relatively brief history of the

human species will face a tragic destiny.

What's the Problem?

According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, the world’s oceans and coasts are highly threatened and subject to rapid environmental change. Major threats to marine and coastal ecosystems include:

* Land-based pollution and euthrophication

* Overfishing, destructive

fishing, and illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing

* Alterations of physical habitats

* Invasions of exotic species

* Global climate change

CONTACTS

Cristiana Pașca

Palmer

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity

413, Saint Jacques Street, suite 800

Montreal QC H2Y 1N9

Canada

Tel: +1 514 288 2220

Fax: +1 514 288 6588

E-Mail: secretariat@cbd.int

Web: www.cbd.int

BIODIVERSITY

COP HISTORY

|

COP

1: 1994 Nassau, Bahamas,

Nov & Dec

|

COP

8: 2006 Curitiba, Brazil, 8

Mar

|

|

COP

2: 1995 Jakarta, Indonesia,

Nov

|

COP

9: 2008 Bonn, Germany,

May

|

|

COP

3: 1996 Buenos Aires, Argentina,

Nov

|

COP

10: 2010 Nagoya, Japan,

Oct

|

|

COP

4: 1998 Bratislava, Slovakia, May

|

COP

11: 2012 Hyderabad, India

|

|

EXCOP:

1999 Cartagena, Colombia, Feb

|

COP

12: 2014 Pyeongchang, Republic of Korea, Oct

|

|

COP

5: 2000 Nairobi, Kenya, May

|

COP

13: 2016 Cancun, Mexico,

2 to 17 Dec

|

|

COP

6: 2002 The Hague, Netherlands,

April

|

COP

14: 2018

Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, 17 to 29 Nov

|

|

COP

7: 2004 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Feb

|

COP

15: 2020 Kunming, Yunnan, China

|

CLIMATE

CHANGE UN COP HISTORY

|

1995

COP 1, BERLIN, GERMANY

1996

COP 2, GENEVA, SWITZERLAND

1997

COP 3, KYOTO, JAPAN

1998

COP 4, BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA

1999

COP 5, BONN, GERMANY

2000:COP

6, THE HAGUE, NETHERLANDS

2001

COP 7, MARRAKECH, MOROCCO

2002

COP 8, NEW DELHI, INDIA

2003

COP 9, MILAN, ITALY

2004

COP 10, BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA

2005

COP 11/CMP 1, MONTREAL, CANADA

2006

COP 12/CMP 2, NAIROBI, KENYA

2007

COP 13/CMP 3, BALI, INDONESIA

|

2008

COP 14/CMP 4, POZNAN, POLAND

2009

COP 15/CMP 5, COPENHAGEN, DENMARK

2010

COP 16/CMP 6, CANCUN, MEXICO

2011

COP 17/CMP 7, DURBAN, SOUTH AFRICA

2012

COP 18/CMP 8, DOHA, QATAR

2013

COP 19/CMP 9, WARSAW, POLAND

2014

COP 20/CMP 10, LIMA, PERU

2015

COP 21/CMP 11, Paris, France

2016

COP 22/CMP 12/CMA 1, Marrakech, Morocco

2017

COP 23/CMP 13/CMA 2, Bonn, Germany

2018

COP 24/CMP 14/CMA 3, Katowice, Poland

2019

COP 25/CMP 15/CMA 4, Santiago, Chile

2020

COP 26/CMP 16/CMA 5, to be announced

|

DESERTIFICATION

COP HISTORY

|

COP

1:

Rome, Italy, 29 Sept to 10 Oct 1997

|

COP

9:

Buenos Aires, Argentina, 21 Sept to 2 Oct 2009

|

|

COP

2:

Dakar, Senegal, 30 Nov to 11 Dec 1998

|

COP

10:

Changwon, South Korea, 10 to 20 Oct 2011

|

|

COP

3:

Recife, Brazil, 15 to 26 Nov 1999

|

COP

11:

Windhoek, Namibia, 16 to 27 Sept 2013

|

|

COP

4:

Bonn, Germany, 11 to 22 Dec 2000

|

COP

12:

Ankara, Turkey, 12 to 23 Oct 2015

|

|

COP

5:

Geneva, Switzerland, 1 to 12 Oct 2001

|

COP

13:

Ordos City, China, 6 to 16 Sept 2017

|

|

COP

6:

Havana, Cuba, 25 August to 5 Sept 2003

|

COP

14:

New Delhi, India, 2 to 13 Sept 2019

|

|

COP

7:

Nairobi, Kenya, 17 to 28 Oct 2005

|

COP

15:

2020

|

|

COP

8:

Madrid, Spain, 3 to 14 Sept 2007

|

COP

16: 2021

|

CONSERVATION

RISK

-

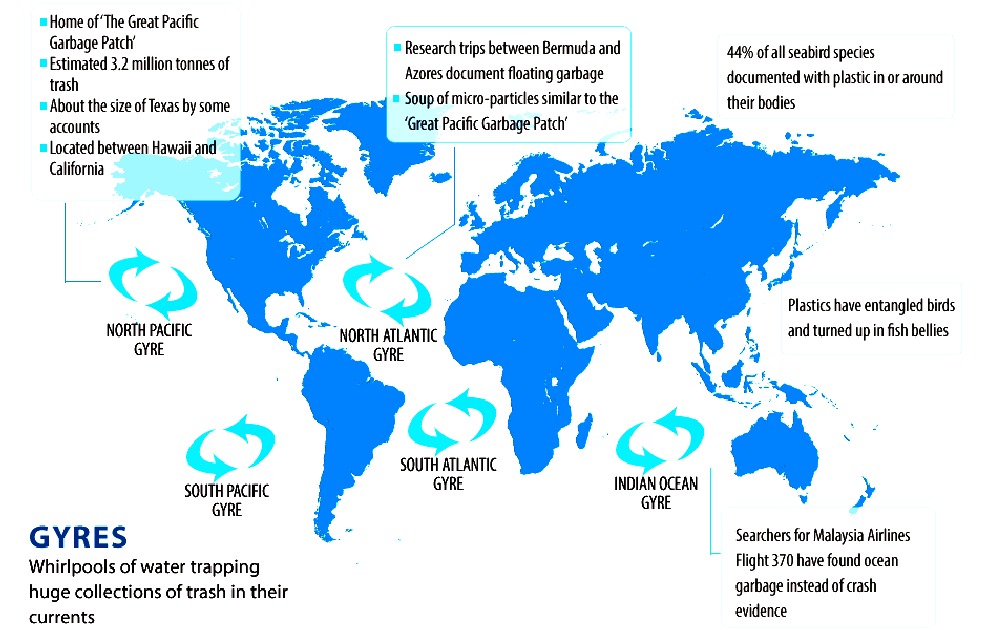

Plastic has accumulated in five ocean hot spots called

gyres, see here in this world map derived from information

published by 5 Gyres. The plastic is laden with toxins that

fish and marine mammals mistake for food and eat - eventually killing them.

Marine pollution is thus a major challenge if we are to ensure that species are

not wiped out.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2010/sep/28/price-biodiversity-species-worth-cop10

https://www.cbd.int/meetings/SBSTTA-01

https://worldoceanreview.com/en/wor-1/marine-ecosystem/biodiversity/

https://www.cbd.int/executive-secretary/

https://www.cbd.int/marine/

This website is

provided on a free basis as a public information service. copyright © Cleaner

Oceans Foundation Ltd (COFL) (Company

No: 4674774) 2019. Solar

Studios, BN271RF, United Kingdom.

COFL is

a company without share capital.

|