|

CIGARETTES

- GOV. HEALTH WARNINGS

PLEASE USE OUR A-Z INDEX

TO NAVIGATE THIS SITE

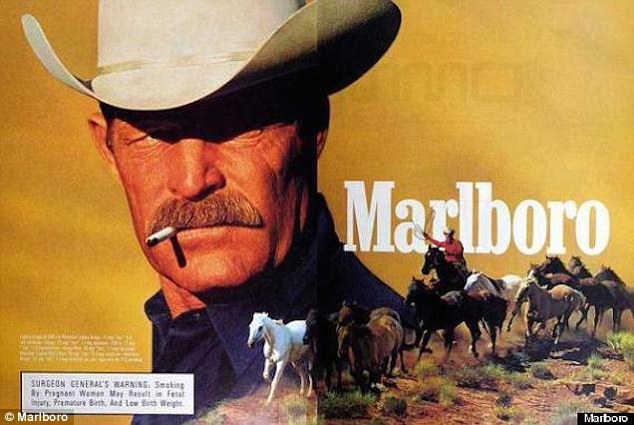

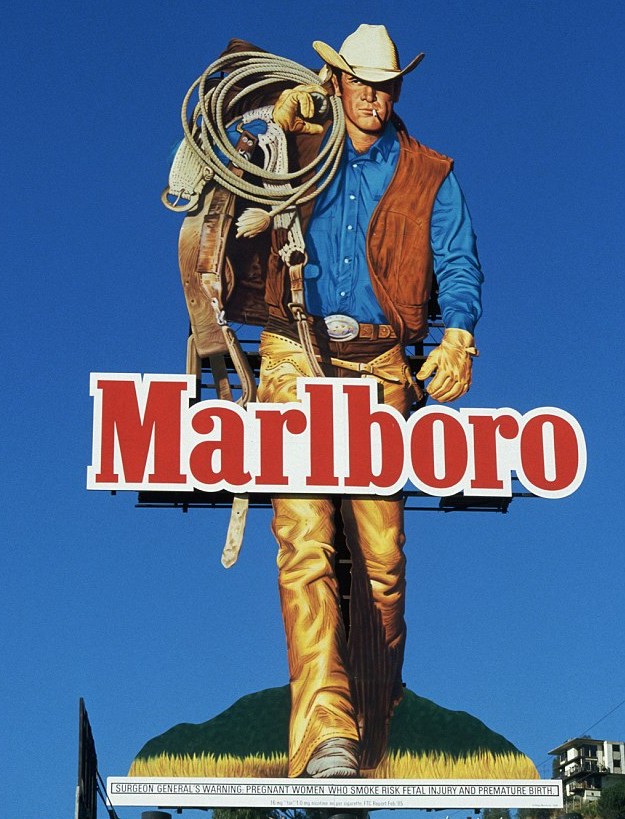

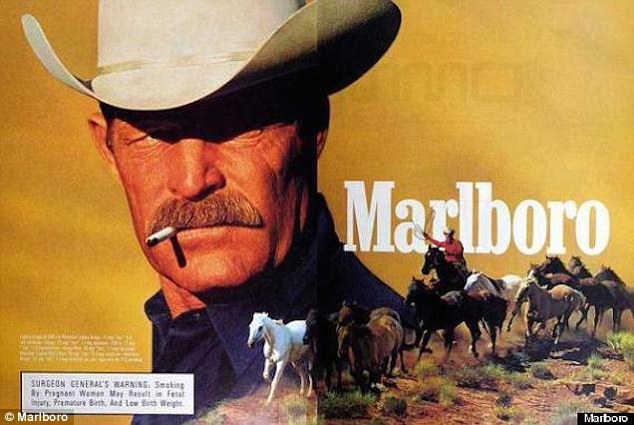

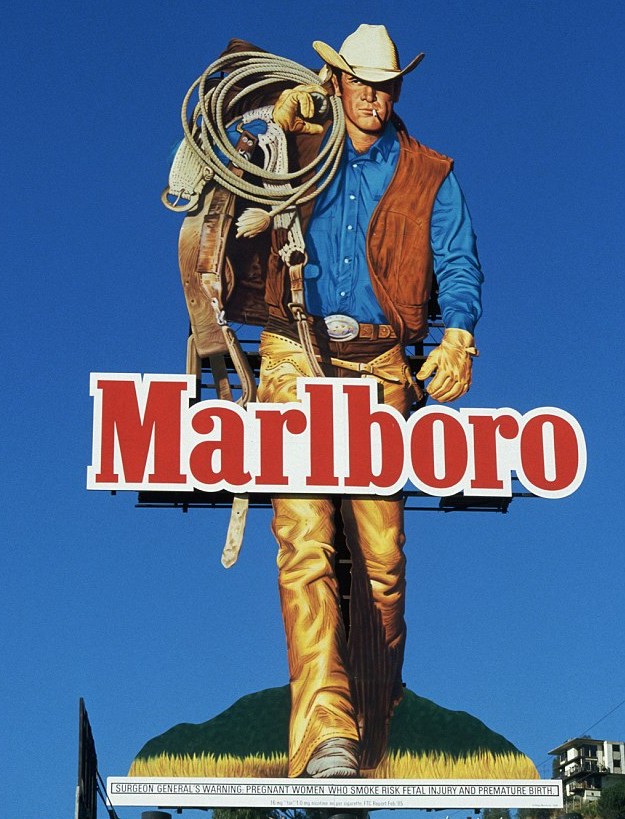

The Malboro Man character - used from 1954 to 1999 in magazine, television and billboard adverts - was portrayed in a natural setting with only a cigarette.

It was initially conceived by Leo Burnett as a way to popularize filtered cigarettes, which at the time were considered a feminine commodity.

Winfield said that he wore his own clothes for shoots and never wore make-up.

The Oklahoma native was one of the last Marlboro Men alive. Some were authentic cowboys like him while others were actors.

Other ex-faces of the tobacco brand include David Millar, who died of emphysema in 1987, and David McLean, who died of lung cancer in 1995.

Another who pushed the product, Wayne McLaren, died before his 52nd birthday in 1992 and Dick Hammer - better known for his role as Captain Hammer in the TV show Emergency! - passed away from lung cancer in 1999, aged 69.

Eric Lawson who played the iconic cigarette-puffing cowboy during the late 1970s passed away aged 72 from respiratory failure last January.

The Marlboro Man was scrapped in the late Nighties, when state governments banned the use of humans or cartoons in U.S. tobacco advertisements.

Winfield was born on July 30, 1929, in Little Kansas, Oklahoma.

Smoking causes approximately 90 percent of all lung

cancer deaths in men and 80 percent of all lung cancer deaths in women. Smoking also causes cancers of the bladder, cervix, esophagus, kidney, larynx, lung, mouth, throat, stomach, uterus, and acute myeloid leukemia. Nearly one-third of all

cancer deaths are directly linked to smoking.

CIGARETTE

COMPANIES KNEW

The

large corporations knew about the link between cancer and

tobacco smoking, but continued to deny this medical fact and

lobby against legislation to warn people about the dangers.

Indeed, they advertised in such a way as to link cigarettes

with a healthy lifestyle. Much the same as PG&E

did with the residents of Hinkley in California, where they

poisoned the town's water supply with chromium.

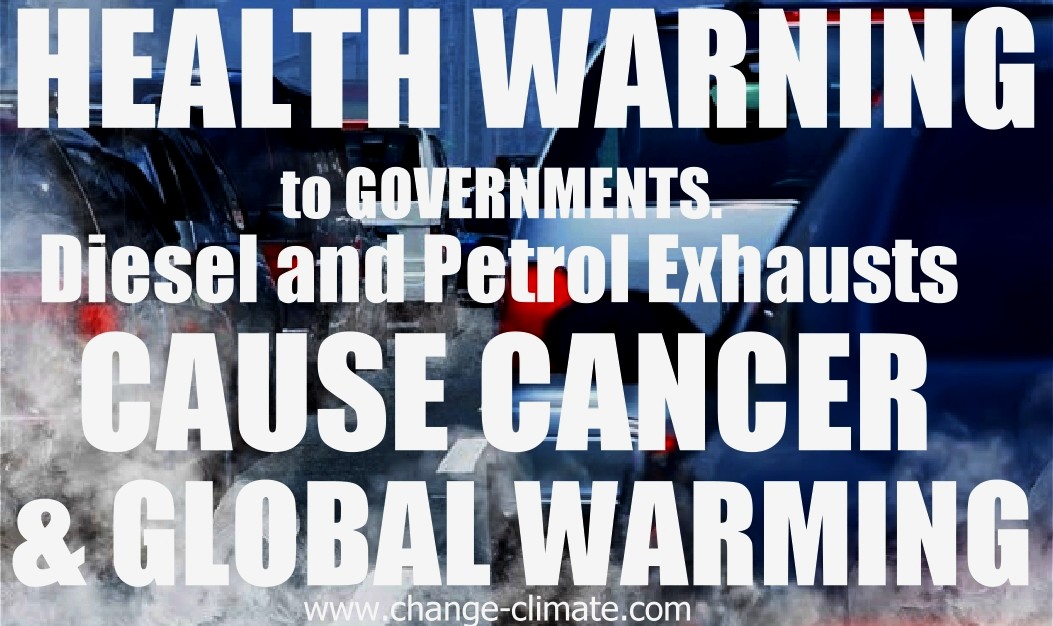

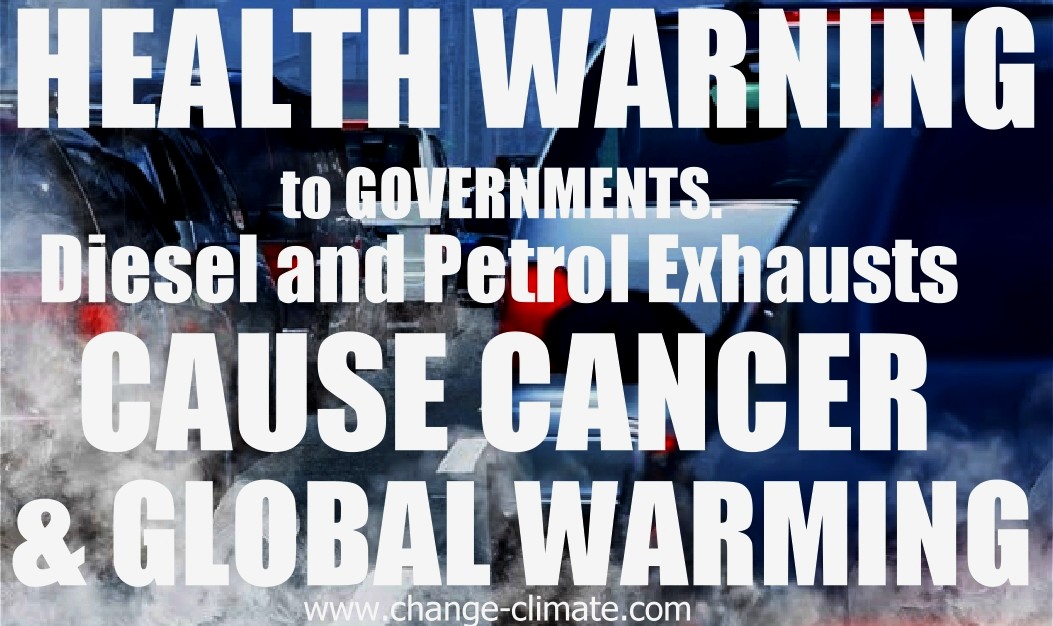

PETROLEUM

AND DIESEL EXHAUST FUMES

The

automobile makers have done exactly the same. They knew about

greenhouse gases but continued to lobby via manufacturers

associations and other contributions, for the right to keep

making and selling vehicles without any health warning

attaching to sales. What about a Government heath warning

about cars and exhaust fumes, with each diesel and petrol car

being forced to carry a label on the dashboard and on the rear

bumper prominently.

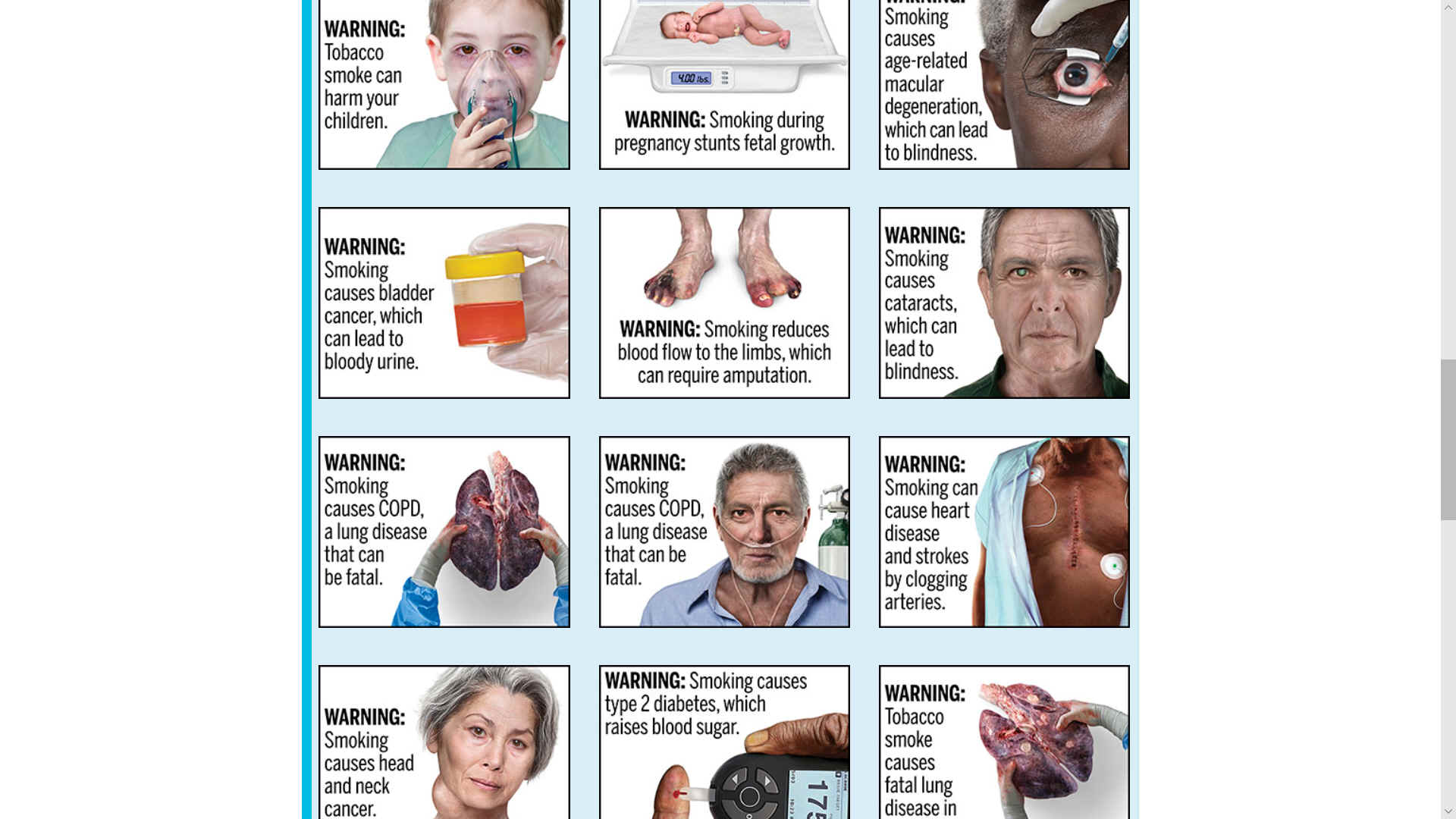

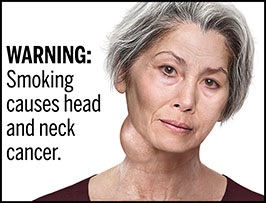

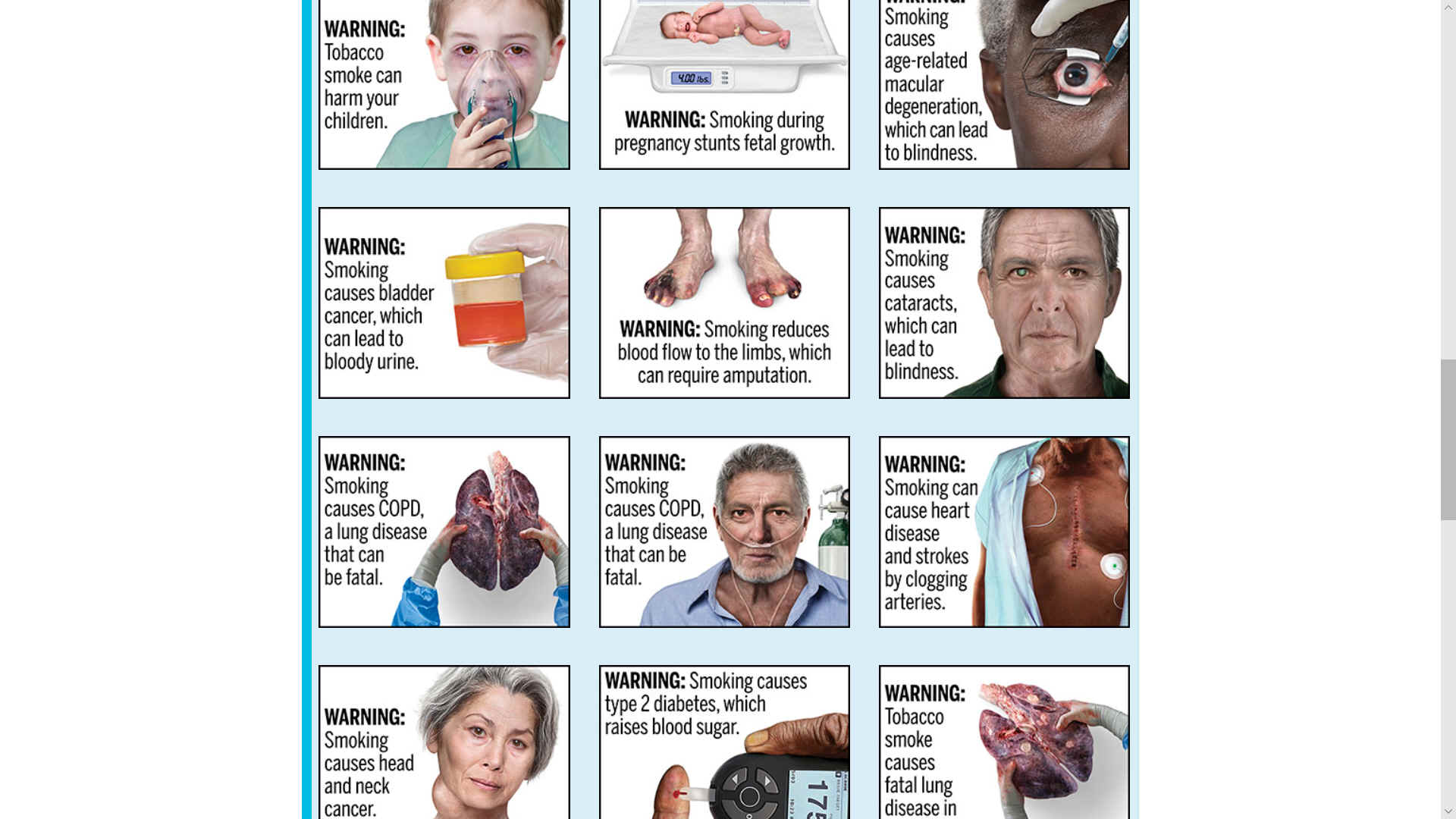

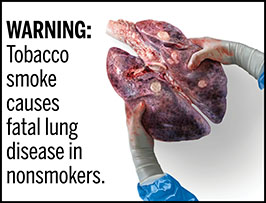

We

are not convinced that these pictures portray the dangers in a

way that is sufficiently shocking to smokers. Smokers are

addicts. Any kind of addiction is hard to kick. It will take a

lot more of the shock factor to stop weak willed addicts from

reaching for the cigarette packet. Some of them simply do not

care until they are undergoing chemotherapy, and by then it is

too late.

PROPOSED

NEW VISUAL WARNINGS

WARNING: Smoking causes mouth and throat cancer (mouth and throat cancer).

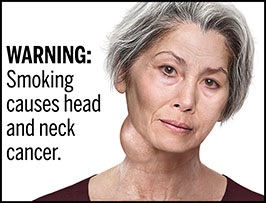

WARNING: Smoking causes head and neck cancer (head and neck cancer).

WARNING: Smoking causes bladder cancer, which can lead to bloody urine (bladder cancer).

WARNING: Smoking during pregnancy causes premature birth (premature birth).

WARNING: Smoking during pregnancy stunts fetal growth (stunts fetal growth).

WARNING: Smoking during pregnancy causes premature birth and low birth weight (low birth weight).

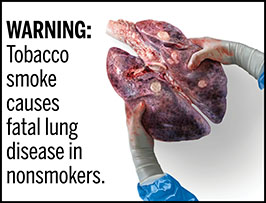

WARNING: Secondhand smoke causes respiratory illnesses in children, like pneumonia (pneumonia).

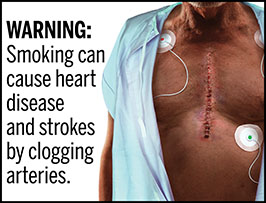

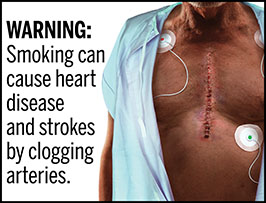

WARNING: Smoking can cause heart disease and strokes by clogging arteries (clogged arteries).

WARNING: Smoking causes COPD, a lung disease that can be fatal (COPD).

WARNING: Smoking causes serious lung diseases like emphysema and chronic bronchitis (emphysema and chronic bronchitis).

WARNING: Smoking reduces blood flow, which can cause erectile dysfunction (erectile dysfunction).

WARNING: Smoking reduces blood flow to the limbs, which can require amputation (amputation).

WARNING: Smoking causes type 2 diabetes, which raises blood sugar (diabetes).

WARNING: Smoking causes age-related macular degeneration, which can lead to blindness (macular degeneration).

WARNING: Smoking causes cataracts, which can lead to blindness (cataracts).

ALTERNATIVE

CULLING - Health

Service budget cuts mean that social care in the community is suffering, so

that the elderly sometimes die from otherwise minor ailments from

complications. The fact is that generally humans are living longer from better

diets, housing and medicines. That is why the retirement age has been raised.

Fish

in the diet has been shown to prolong life over meat eaters (red meat in

particular) one reason the Japanese have so many centenarians. It could be

argued that by not cleaning the oceans, population growth might be halted in

the longer term when people develop cancer as a result of eating toxic fish.

An unkind notion and inhumane, but surely treating cancer patients in large

numbers will cost more than cleaning the oceans - unless future budget cuts

mean suspending treatments - and that is the secret agenda.

Spending

on cancer research might go to offset the rising toxicity levels of wild fish

and consequential human suffering. The EU have pledged sums on their Horizon

Europe budget for cancer research.

There

are as yet no Government Health Warnings as to toxic

biomagnification in seafoods, caused by marine plastic.

FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION (AGENCY) PROPOSED CHANGES

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA, the Agency, or we) is issuing a proposed rule to establish new required cigarette health warnings for cigarette packages and advertisements. The proposed rule would implement a provision of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (Tobacco Control Act) that requires FDA to issue regulations requiring color graphics depicting the negative health consequences of smoking to accompany new textual warning statements. The Tobacco Control Act amends the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act (FCLAA) of 1965 to require each cigarette package and advertisement to bear one of the new required warnings. This proposed rule, once finalized, would specify the color graphics that must accompany the new textual warning statements. FDA is proposing to take this action to promote greater public understanding of the negative health consequences of cigarette smoking.

Table of Contents

I. Executive Summary

A. Purpose of the Proposed Rule

B. Summary of the Major Provisions of the Proposed Rule

C. Legal Authority

D. Costs, Benefits, and Informational Effects

Table of Abbreviations/Commonly Used Acronyms in This Document

II. Background

A. Need for the Regulation

B. History of the Rulemaking

C. Incorporation by Reference

III. Legal Authority

IV. Cigarette Use in the United States and the Resulting Health Consequences

A. Smoking Prevalence and Initiation in the United States

B. Negative Health Consequences of Smoking

V. Data Concerning Cigarette Health Warnings

A. The Current 1984 Surgeon General's Warnings Are Inadequate

B. Cigarette Health Warnings That Are Noticeable, Lead to Learning, and Increase Knowledge Will Promote Public Understanding About the Negative Health Consequences of Smoking

VI. FDA's Process for Developing and Testing the Proposed Cigarette Health Warnings

A. Review of the Negative Health Consequences of Cigarette Smoking

B. Developing Revised Textual Warning Statements

C. FDA's Consumer Research Study on Revised Textual Warning Statements

D. Developing and Testing Images Depicting the Negative Health Consequences of Smoking To Accompany the Textual Warning Statements

E. FDA's Consumer Research Study on New Cigarette Health Warnings

VII. FDA's Proposed Required Warnings

A. FDA's Proposed Required Warnings

VIII. First Amendment Considerations

IX. Description of the Proposed Rule

A. General Provisions (Proposed Subpart A)

B. Required Warnings for Cigarette Packages and Advertisements (Proposed § 1141.10)

C. Misbranding of Cigarettes (Proposed § 1141.12)

X. Proposed Effective Dates

XI. Severability and Other Considerations

XII. Preliminary Economic Analysis of Impacts

XIII. Analysis of Environmental Impact

XIV. Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995

XV. Federalism

XVI. Consultation and Coordination With Indian Tribal Governments

XVII. References

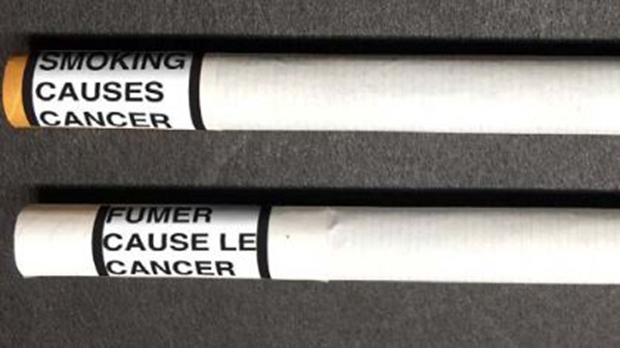

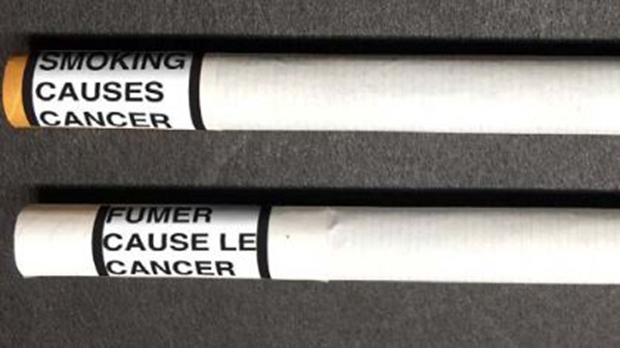

OCTOBER

30 2018 - Canada could become the first country in the world to require cigarette manufacturers to include warnings about the dangers of tobacco on individual cigarettes.

The federal government has launched a consultation process looking at regulations around warnings on tobacco products.

One of the most significant ideas being floated in the consultation is a new requirement for “smoking causes cancer” or similar wording to be included on individual cigarettes. Currently, Canada only mandates that such warnings be placed on or inside cigarette packaging.

“There is recent but limited research showing that health warnings placed directly on a product, such as cigarettes, could be effective in making the product less appealing to users,” a government consultation document reads.

Rob Cunningham, a senior policy analyst for the Canadian Cancer Society, describes the proposal as a “logical next step” for health warning requirements.

“It’s an incredibly cost-effective way to reach every smoker every day with the health message,” he told CTVNews.ca.

In addition to potentially causing people to rethink their cigarette use, Cunningham sees a benefit for law enforcement in the proposal. He said it would make it easier for police to detect illegally produced cigarettes, which authorities believe to be a major player in Canada’s tobacco industry.

The government is also looking at requiring warning labels on cigarette packages to change every year. Federally mandated warning labels were last modified in 2012.

“It’s already been six years since the last warnings appeared. To keep them fresh increases their impact,” Cunningham said.

Other ideas under consideration include adding brighter colours and eye-catching cartoons to existing warning labels and ensuring the various warnings on each package follow the same theme and deliver the same message.

Labels may also become mandatory for tobacco products which do not currently need them, including water pipe tobacco and heated tobacco products.

The proposals were open to public feedback until Jan. 4, 2019. The federal government estimates that 45,000 Canadians die due to smoking-related health issues each year.

I. Executive Summary

A. Purpose of the Proposed Rule

This proposed rule would establish new required cigarette health warnings for cigarette packages and advertisements. These new cigarette health warnings would consist of textual warning statements accompanied by color graphics depicting the negative health consequences of cigarette smoking. The new cigarette health warnings, once finalized, would appear prominently on cigarette packages and in cigarette advertisements, occupying the top 50 percent of the area of the front and rear panels of cigarette packages and at least 20 percent of the area at the top of cigarette advertisements.

Cigarette smoking remains the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the United States and is responsible for more than 480,000 deaths per year. Smoking causes more deaths each year than human immunodeficiency virus, illegal drug use, alcohol use, motor vehicle injuries, and firearm-related incidents combined. In developing this proposed rule, FDA determined that the public holds misperceptions about the health risks caused by smoking and that warning statements focused on less-known health consequences of smoking paired with concordant color graphics would promote greater public understanding of the risks associated with cigarette smoking, especially given that the existing Surgeon General's warnings currently used in the United States have been shown to go unnoticed and be “invisible.” For the reasons discussed in the preamble to this proposed rule, FDA has determined that the proposed new cigarette health warnings will advance the Government's interest in promoting greater public understanding of the negative health consequences of cigarette smoking.

B. Summary of the Major Provisions of the Proposed Rule

This proposed rule would establish new required warnings to appear on cigarette packages and in cigarette advertisements. The proposed rule would implement a provision of the Tobacco Control Act that requires FDA to issue regulations requiring color graphics depicting the negative health consequences of smoking to accompany new textual warning statements. The Tobacco Control Act amends the FCLAA to require each cigarette package and advertisement to bear one of the new required warnings. These new cigarette health warnings would consist of textual warning statements accompanied by color graphics, in the form of concordant photorealistic images, depicting the negative health consequences of cigarette smoking. As required under the FCLAA, the new cigarette health warnings, once finalized, would appear prominently on cigarette packages and in cigarette advertisements, occupying the top 50 percent of the area of the front and rear panels of cigarette packages and at least 20 percent of the area at the top of cigarette advertisements.

In addition, as required under the FCLAA, the proposed rule would establish marketing requirements that would include the random display and distribution of the required warnings for cigarette packages and quarterly rotations of the required warnings for cigarette advertisements. A tobacco product manufacturer, distributor, or retailer would be required to submit a plan for the random and equal display and distribution of the required warnings on packages and the quarterly rotation in advertisements for approval by FDA. In addition, the proposed rule would require each tobacco product manufacturer required to randomly and equally display and distribute warnings on packaging or quarterly rotate warnings on advertisements in accordance with an FDA-approved plan, to maintain a copy of the FDA-approved plan, and to make the plan available for inspection and copying by officers and employees of FDA.

FDA developed the new cigarette health warnings included in this proposed rule through a science-based, iterative research process. The proposed warnings are intended to promote greater public understanding of the negative health consequences of cigarette smoking.

C. Legal Authority

This proposed rule is being issued in accordance with sections 201 and 202 of the Tobacco Control Act (Pub. L. 111-31), which amend section 4 of the FCLAA (15 U.S.C. 1333). This proposed rule is also being issued based upon FDA's authorities related to misbranded tobacco products under sections 903 (21 U.S.C. 387c); FDA's authorities related to records and reports under section 909 (21 U.S.C. 387i); and FDA's rulemaking and inspection authorities under sections 701 (21 U.S.C. 371), 704 (21 U.S.C. 374), and 905(g) (21 U.S.C. 387e(g)) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act).

D. Costs, Benefits, and Informational Effects

The proposed new cigarette health warnings would promote greater public understanding of the negative health consequences of cigarette smoking by presenting information about the health risks of smoking to smokers and nonsmokers in a format that helps people better understand these consequences. Despite the informational effects of this proposed rule, there is a high level of uncertainty around quantitative economic benefits at this time, so we describe them qualitatively. The cost of this proposed rule consists of initial and recurring labeling costs associated with changing cigarette labels to accommodate the new cigarette health warnings, design and operation costs associated with the random and equal display and distribution of required cigarette health warnings for cigarette packages and quarterly rotations of the required warnings for cigarette advertisements, advertising-related costs, and costs associated with government administration and enforcement of the rule. We estimate that, at the mean, the present value of the costs of this proposed rule is about $1.6 billion using a three percent discount rate and roughly $1.2 billion using a seven percent discount rate (2018$). If the information provided by the cigarette health warning on each cigarette package was valued at about $0.01 (for every pack sold annually nationwide), then the benefits that would be generated by the proposed rule would equal or exceed the estimated annual costs.

II. Background

A. Need for the Regulation

To help inform consumers of the potential hazards of cigarette smoking, Congress passed the FCLAA that required that a printed text-only warning appear on cigarette packages (Pub. L. 89-92). The 1965 warning requirement was modified by later amendments to the FCLAA, including the Comprehensive Smoking Education Act of 1984 (Pub. L. 98-474), which extended the warning requirement to cigarette advertising and updated the one warning to four warnings, frequently referred to as the Surgeon General's warnings.

The FCLAA has required the inclusion of text-only warnings on cigarette packages and in cigarette advertisements for many years. As discussed in detail in section V.A, there is considerable evidence that the Surgeon General's warnings go largely unnoticed and unconsidered by both smokers and nonsmokers. These warnings, which have not changed in nearly 35 years, have been described as “invisible” (Ref. 1) and fail to convey relevant information in an effective way (Ref. 2 at p. 291). The Surgeon General's warnings also do not include any color graphics.

In 2009, in enacting the Tobacco Control Act, Congress further amended the FCLAA and directed FDA to issue new cigarette health warnings that would include a graphic component depicting the negative health consequences of smoking to accompany the new textual warnings (section 201 of the Tobacco Control Act). In enacting this legislation, Congress also provided that FDA may adjust the warnings if FDA found that such a change would promote greater public understanding of the risks associated with the use of tobacco products (section 202 of the Tobacco Control Act).

Approximately 34.3 million U.S. adults smoke cigarettes (defined as smoking at least 100 cigarettes during their lifetime and now smoking cigarettes every day or some days) and nearly 1.4 million U.S. youth (aged 12-17 years) smoke cigarettes (defined as past 30-day use) (Refs. 5 and 6). Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health demonstrate that, on average, each day in the United States, about 2,000 youth under age 18 smoke their first cigarette, and 320 youth become daily cigarette smokers (Ref. 7).

The health risks associated with cigarette smoking are significant. Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the United States and is responsible for more than 480,000 deaths per year (Ref. 8). Smoking causes more deaths each year than human immunodeficiency virus, illegal drug use, alcohol use, motor vehicle injuries, and firearm-related incidents combined (Refs. 9 and 10). Over 16 million Americans alive today live with disease caused by smoking cigarettes (Ref. 8). In addition to lung cancer, heart disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), smoking also causes numerous other serious health conditions that are less-known effects of smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke, including many types of cancer, premature birth, low birth weight, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), respiratory illnesses, clogged arteries, reduced blood flow, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and vision conditions such as age-related macular degeneration and cataracts (Ref. 8).

In developing this proposed rule, FDA carefully examined the scientific literature, including the 2014 Surgeon General's Report (Ref. 8), which identified 11 more health conditions that have been established to have sufficient evidence to infer a causal link to cigarette smoking—the highest level of evidence of causal inferences from the criteria applied in the Surgeon General's Reports. Those health conditions examined in the 2014 Surgeon General's Report are in addition to the more than forty unique health consequences already classified in previous Surgeon General's Reports as being caused by smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke. Additional findings in the scientific literature demonstrate that the U.S. public—including youth and adults, smokers and nonsmokers—holds misperceptions about the health risks caused by smoking (Refs. 3 and 11-16). Through its review of the scientific literature, as well as the Agency's science-based, iterative research and development process (described in sections V and VI), FDA determined that having warning statements focused on less-known health consequences of smoking accompanied by photorealistic images can promote greater public understanding of the risks associated with cigarette smoking, especially given the unnoticed and “invisible” 1984 Surgeon General's warnings currently used in the United States (see section V.A).

Therefore, consistent with section 4 of the FCLAA (as amended by sections 201 and 202 of the Tobacco Control Act), we are proposing a set of textual warning label statements, to be accompanied by concordant color graphics depicting the negative health consequences of smoking, to appear on cigarette packages and in cigarette advertisements. Specifically, we are proposing to replace part 1141 to Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR part 1141), and the new part 1141 would require new cigarette health warnings [1] on cigarette packages and in cigarette advertisements. These new cigarette health warnings would consist of up to 13 textual warning label statements accompanied by color graphics depicting the negative health consequences of smoking. As required by section 4 of the FCLAA, the new cigarette health warnings would appear prominently on packages and in advertisements, occupying the top 50 percent of the area of the front and rear panels of cigarette packages and at least 20 percent of the area at the top of cigarette advertisements.

As described in section VII, FDA has determined that the proposed new cigarette health warnings will advance the Government's interest in promoting greater public understanding of the negative health consequences of cigarette smoking.

B. History of the Rulemaking

In the Federal Register of June 22, 2011 (76 FR 36628), FDA issued a final rule entitled “Required Warnings for Cigarette Packages and Advertisements,” which specified nine images to accompany the nine textual warning statements for cigarettes set out in the Tobacco Control Act. The final rule was challenged in court, and on August 24, 2012, the United States Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia vacated the rule and remanded the matter to the Agency. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. v. Food & Drug Administration, 696 F.3d 1205 (D.C. Cir. 2012), overruled on other grounds by Am. Meat Inst. v. U.S. Dep't of Agric., 760 F.3d 18, 22-23 (D.C. Cir. 2014) (en banc). On December 5, 2012, the Court denied the Government's petition for panel rehearing and rehearing en banc, and the Government decided not to seek further review of the Court's ruling. In a letter to Congress on March 15, 2013, the U.S. Attorney General reported FDA's intention to undertake research to support a new rulemaking consistent with the Tobacco Control Act (Ref. 17).

Central to FDA's work since that time has been evaluating how to address the D.C. Circuit's critiques of the prior rule and carefully considering how to develop a research plan and rulemaking process that will provide a robust record for a new cigarette health warnings rule. Through extensive legal, scientific, and regulatory analyses, FDA developed a science-based, iterative research process for developing new cigarette health warnings to put forth in this proposed rule that would advance the Government's substantial interest in promoting greater public understanding of the negative health consequences of smoking. Because these cigarette health warnings, as shown through the robust scientific evidence described in detail in sections VI-VII, are factual and accurate, advance the substantial Government interest in promoting greater public understanding of the negative health consequences of smoking, and are not unduly burdensome, FDA believes the warnings would pass a First Amendment analysis under Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel, 471 U.S. 626 (1985) (or, if applied, Central Hudson Gas & Elec. Corp. v. Pub. Serv. Comm'n, 447 U.S. 557 (1980)). After reviewing public comments and weighing additional scientific, legal, and policy considerations, FDA intends to finalize some or all of the 13 cigarette health warnings proposed in this rule.

C. Incorporation by Reference

FDA is proposing to incorporate by reference certain material entitled “Required Cigarette Health Warnings.” We have included an electronic portable document format (PDF) file, containing the proposed required warnings, as a reference in the docket (Ref. 18). Any final rule would provide information on how to obtain the final electronic, layered design files for each required warning, as well as technical specifications to help regulated entities appropriately select, crop, and scale the warnings to ensure the required warnings are accurately reproduced across various sizes and shapes of cigarette packages and cigarette advertisements. FDA would also provide instructions for how to access this material (e.g., via download through FDA's website or a file transfer protocol website). Any material incorporated by reference must meet the Office of the Federal Register's (OFR) requirements for incorporating material by reference (5 U.S.C 552(a) and 1 CFR part 51).

III. Legal Authority

The Tobacco Control Act was enacted on June 22, 2009, amending the FD&C Act and providing FDA with the authority to regulate the manufacture, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products to protect the public health and to reduce tobacco use by minors. Section 201 of the Tobacco Control Act amends section 4 of the FCLAA to require that nine new health warning statements appear on cigarette packages and in cigarette advertisements and directs FDA to “issue regulations that require color graphics depicting the negative health consequences of smoking” to accompany the nine new health warning statements. Under section 201 of the Tobacco Control Act, FDA may adjust the type size, text, and format of the cigarette health warnings as FDA determines appropriate so that both the color graphics and the accompanying textual warning label statements are clear, conspicuous, and legible and appear within the specified area (15 U.S.C. 1333(d)).

Section 202(b) of the Tobacco Control Act also amends section 4 of the FCLAA to add a new subsection [2] that permits FDA to, after providing notice and an opportunity for the public to comment, adjust the format, type size, color graphics, and text of any of the label requirements, or establish the format, type size, and text of any other disclosures required under the FD&C Act, if such a change would promote greater public understanding of the risks associated with the use of tobacco products. Such adjustments, including adjustments to the text of some of the warning statements and to the number of proposed required warnings, are included as part of this proposed rule.

These requirements are supplemented by the FD&C Act's misbranding provisions, which require that product labeling and advertising include required warnings. For example, a tobacco product is deemed misbranded under section 903(a)(1) or (a)(7)(A) of the FD&C Act if its labeling or advertising is false or misleading in any particular. Under section 201(n) of the FD&C Act (21 U.S.C. 321(n)), in determining whether labeling or advertising is misleading, FDA considers, among other things, the failure to reveal material facts concerning the consequences that may result from the customary or usual use of the product. Similarly, under section 903(a)(8)(B) of the FD&C Act, a tobacco product is deemed misbranded unless the manufacturer, packer, or distributor includes in all advertisements and other descriptive printed matter, which FDA interprets as including packages, a brief statement of, among other things, the relevant warnings. Under section 701(a) of the FD&C Act, FDA has authority to issue regulations for the efficient enforcement of the FD&C Act, and sections 704 and 905(g) provide FDA with general inspection authority.

Section 909 of the FD&C Act authorizes FDA to require tobacco product manufacturers to establish and maintain records, make reports, and provide such information as the Agency may by regulation reasonably require to ensure that a tobacco product is not adulterated or misbranded and to otherwise protect public health.

IV. Cigarette Use in the United States and the Resulting Health Consequences

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the United States and is responsible for more than 480,000 deaths per year (Ref. 8). Smoking causes more deaths each year than human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), illegal drug use, alcohol use, motor vehicle injuries, and firearm-related incidents combined (Refs. 9 and 10). In addition to lung cancer, heart disease, and COPD, smoking also causes numerous other serious health conditions, including many types of cancer, premature birth, low birth weight, SIDS, respiratory illnesses, clogged arteries, reduced blood flow, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and vision conditions such as age-related macular degeneration and cataracts (Ref. 8).

A. Smoking Prevalence and Initiation in the United States

Approximately 34.3 million U.S. adults and nearly 1.4 million U.S. youth (aged 12-17 years) smoke cigarettes (Refs. 5 and 6). Over 16 million Americans alive today live with disease caused by smoking cigarettes (Ref. 8). Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health demonstrate that, on average, each day in the United States, about 2,000 youth under age 18 smoke their first cigarette, and 320 youth become daily cigarette smokers (Ref. 7).

Cigarettes remain the most commonly used tobacco product in the United States among adults, and a substantial percentage of U.S. adults are cigarette smokers (Ref. 5). Although cigarette smoking prevalence has generally declined over the past several decades, results from the 2017 National Health Interview Survey indicate that approximately 34.3 million U.S. adults (or 14.0 percent of the U.S. adult population) are current cigarette smokers (Ref. 5). Among these adult smokers, the vast majority—75 percent, or approximately 25.7 million people—smoke every day. Smoking prevalence remains higher than the national average among certain demographic subgroups of the adult population. For example, among adults with differing levels of education, the highest prevalence rates have been observed in adults with lower education levels. Data indicate that 36.8 percent of adults with a General Education Development (GED) certificate and 23.1 percent of adults with less than a high school diploma were current smokers in 2017, compared with 7.1 percent of adults with a college degree and 4.1 percent of adults with a graduate degree (Ref. 5).

The National Youth Tobacco Survey is a nationally representative survey of U.S. students attending public and private schools in grades 6 through 12. The 2018 National Youth Tobacco Survey data showed that past 30-day smoking prevalence among high school students was 8.1 percent, representing 1.2 million young people, of which 23.1 percent were frequent smokers (defined as cigarette use on 20 or more of the past 30 days) (Ref. 6). The data also showed that past 30-day prevalence among middle school students was 1.8 percent, representing 200,000 youth, of which 19.7 percent were frequent smokers (Ref. 6). These youth who have smoked in the past 30 days are at particular risk of becoming nicotine dependent through smoking. In one study, 22 percent of 7th grade students who had initiated occasional smoking reported a symptom of nicotine dependence within 4 weeks after starting to smoke at least once per month (Ref. 19). Among 60 students with symptoms of nicotine dependence, 62 percent reported experiencing their first symptom before smoking daily or began smoking daily only upon experiencing their first symptom (Ref. 19). An analysis of the 2012 National Youth Tobacco Survey found that a substantial proportion of adolescents that use tobacco report symptoms of nicotine dependence, even with low levels of use (Ref. 20). Among adolescents who reported only smoking cigarettes, 42.6 percent reported having strong cravings to smoke, a symptom of nicotine dependence, in the past 30 days (Ref. 20).

B. Negative Health Consequences of Smoking

Cigarette smoking remains the leading cause of preventable disease and death in the United States. The 2014 Surgeon General's Report found that cigarette smoking was responsible for an average of over 480,000 premature deaths in the United States each year from 2005 to 2009, of which almost 440,000 occurred because of active smoking (Ref. 8). The report also found that cigarette smoking was directly responsible for 163,700 deaths from cancer, 160,600 deaths from circulatory conditions, and 113,100 deaths from pulmonary diseases each year. As a consequence of secondhand smoke exposure, there were an additional 7,330 deaths from lung cancer and 33,950 deaths from coronary heart disease annually. Cigarette smoking therefore accounted for 87 percent of deaths from lung cancer, 79 percent of deaths from COPD, and 32 percent of deaths from coronary heart disease in the United States from 2005 to 2009.

It has also been estimated that approximately 14 million U.S. adults had serious medical conditions attributable to cigarette smoking in 2009 (Ref. 21). COPD accounted for the largest number of these conditions with an estimated 7.5 million Americans living with this condition because of smoking. Other serious conditions for which smoking-attributable morbidity was estimated included heart attack (2.3 million cases), cancer (1.3 million cases), and stroke (1.2 million cases) (Ref. 21). Because individuals can live for many years with some of these health conditions and, in some cases, smoking-attributable health conditions can develop after a smoker has stopped smoking (e.g., lung cancer) (e.g., Ref. 22), the morbidity burden from cigarette smoking is expected to remain high.

Cigarette smoking also causes many other health conditions; however, the link between smoking and these conditions is less known to the public. For example, a meta-analysis found that current smokers are twice as likely as never smokers to have age-related macular degeneration (Ref. 23), a degenerative condition of the tissues of the retina. Current smokers have also been found to have approximately 50 percent higher risk of age-related cataracts than never smokers according to meta-analysis (Ref. 24). Cigarette smokers have an increased risk of numerous circulatory and metabolic conditions. Another meta-analysis found that smokers have approximately 45 percent higher risk of diabetes than nonsmokers (Ref. 25). It is estimated that 1.8 million Americans have diabetes due to smoking (Ref. 21) and that 9,000 Americans die of diabetes due to smoking each year (Ref. 8). Current smokers are nearly three times as likely as never smokers to have peripheral arterial disease, a condition that can lead to amputation of limbs (Ref. 26). Male smokers have been found to be 40 to 50 percent more likely to have erectile dysfunction due to diminished blood flow than nonsmokers (Refs. 27 and 28). Smokers also have increased risk of many types of cancer, beyond lung cancer. For example, current smokers have been found to have almost four times the risk of bladder cancer as never smokers (Ref. 29), and it has been estimated that smoking is responsible for 5,000 bladder cancer deaths in the United States each year (Ref. 30). Smoking has also been established to cause cancers of the head and neck, such as oral cancer.

The American Cancer Society's Cancer Prevention Study II found elevated relative risks (i.e., the risk of the conditions among smokers compared to nonsmokers) for current smoking of 10.9 for males and 5.1 for females for lip, oral cavity, and pharyngeal cancers (i.e., male smokers have 10.9 times higher risk of developing these cancers than male nonsmokers, and female smokers have 5.1 times higher risk of developing these cancers than female nonsmokers) and 14.6 for males and 13.0 for females for laryngeal cancer (Ref. 31). These increased risks result in approximately 4,900 deaths from lip, oral, and pharyngeal cancers and 3,000 deaths from laryngeal cancer from smoking in the United States each year (Ref. 30).

Secondhand smoke exposure also increases disease risks, especially among infants and children. For example, secondhand smoke exposure has been found to be causally linked to stroke, lung cancer, and other disease in adults and lower respiratory illness in children (Ref. 8). Additionally, maternal smoking (i.e., smoking while pregnant) has been found to be associated with low birth weight (Ref. 32) and fetal growth restriction (Ref. 33). The California Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has estimated that there are 24,500 cases of low birth weight due to maternal exposure to secondhand smoke (referred to as “environmental tobacco smoke”) in the United States per year (Ref. 34). Other health consequences in children exposed to secondhand smoke include middle ear disease, respiratory symptoms, impaired lung function, lower respiratory illness, and SIDS, and it is estimated that 400 infants die from SIDS due to exposure to secondhand smoke each year (Ref. 8).

V. Data Concerning Cigarette Health Warnings

A. The Current 1984 Surgeon General's Warnings Are Inadequate

As described in this section, cigarette warnings in the United States have not changed in nearly 35 years, and the size and location of the warnings have not changed in more than 50 years. The unchanged content of these health warnings, as well as their small size and lack of an image, severely impairs their ability to convey relevant information about the negative health consequences of cigarette smoking in an effective way (Ref. 2). Research has repeatedly illustrated that the current 1984 warnings used in the United States frequently go unnoticed or fail to convey relevant information regarding health risks (Ref. 4). Moreover, although many members of the U.S. public possess some general knowledge of the harms of smoking, substantial gaps in knowledge remain, and smokers have misinformation regarding cigarettes and the negative health effects of smoking (Refs. 36 and 37).

Cigarette packages and advertisements can serve as an important channel for communicating health information to broad audiences that include both smokers and nonsmokers. Daily smokers, who in 2016 averaged 14.1 cigarettes per day, are potentially exposed to the warnings on packages over 5,100 times per year, and, because these packages are not always concealed and are often visible to those other than the person carrying the package, warnings on those packages are potentially viewed by many others, including nonsmokers (Refs. 38 and 40). Smokers and nonsmokers, including adolescents, also are frequently exposed to cigarette advertising appearing in a range of marketing channels, including print and digital media, outdoor locations, and in and around retail establishments where tobacco products are sold (Refs. 42 and 43). The importance of cigarette advertising is reflected in cigarette companies' substantial annual expenditures for cigarette advertising and promotion in the United States, which totaled $1.3 billion in 2017 (not including the price discounts paid to cigarette retailers and wholesalers to help lower the price of cigarettes to consumers) (Ref. 41). Retail displays of cigarette packages and other in-store cigarette advertisements are typically located in areas of a store that are seen by a majority of consumers, such as near the checkout counter, and provide significant opportunities for communicating with smokers and nonsmokers (Refs. 44-47). The inclusion of health warnings on cigarette packages and in advertisements therefore can provide a critical opportunity to help smokers and nonsmokers of all ages better understand the negative health consequences of smoking. Prominent displays of such warnings are more likely to be noticed and to impact learning and knowledge than non-prominent displays (Refs. 3, 4, 39, 48-50). The World Health Organization's (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control has also recommended large pictorial cigarette warnings on tobacco products as a way to increase public awareness about the negative health effects of tobacco use (Ref. 51).

Given the extreme risks cigarette smoking poses to the public health, new warnings, as described in detail below and as included in this proposed rule, are critical to promote greater public understanding of the negative health consequences of cigarette smoking.

LONDON

FEBRUARY 4 2020 - The chair of an independent inquiry into how a prominent British breast surgeon was able to perform unnecessary operations for years concluded Tuesday that more than 1,000 patients might have been affected by a "dysfunctional" system that did not keep patients safe.

In 2017, a jury found rogue surgeon Ian Paterson guilty of 17 counts of wounding with intent to cause grievous bodily harm and three counts of unlawful wounding. Prosecutors say the doctor lied to patients or exaggerated their risk of cancer to persuade them to have surgery.

But Paterson's patients demanded a more thorough reckoning to prevent such situations from ever happening again. The examination of Paterson's actions concluded that patients were let down for many years both by Britain's National Health Service and by private medical insurance and workers. The Rev. Graham James, the inquiry's chair, said opportunities to stop the doctor's behaviour were repeatedly missed by a system characterized by "wilful blindness."

"Eight years passed between medical professionals raising concerns about Ian Paterson's medical practice and his suspension," James said. "He was given the benefit of the doubt time and time again, undeservedly. And the consequences for the patients have been terrible."

Asked how many patients might have been affected by Paterson's malpractice, James confirmed it could "certainly" be more than 1,000.

Hundreds of Paterson's patients were recalled in 2012 after concerns about unnecessary or incomplete operations. Nine women and one man testified about the procedures during his trial, which dealt with surgeries between 1997 and 2011.

Initially sentenced to 15 years in prison, Court of Appeal judges later increased his sentence to 20 years.

Paterson owned a luxury home in Birmingham, in central England, as well as properties in Cardiff, Manchester and the United States, West Midlands police said.

Victims who accused him of playing God with their lives included Deborah Douglas, a mother-of-three who underwent an entirely unnecessary mastectomy that left her in "horrendous" pain. At her home in Birmingham, she keeps memorial cards from the funerals of some other Paterson patients.

"We want recommendations that change the system that allowed Paterson to get away with it, because basically, people have died," she said. "He left breast tissue behind, and that led to patients' deaths."

Among his recommendations, James urged the creation of an "accessible and intelligible" single repository of performance data

- a one-stop shop for patients. Paterson did not accept the inquiry's offer to comment.

The

UK employed the Dental Estimates Board to track unnecessary

tooth operations such as fillings and extractions, where it

appears that such occurrences are not that uncommon. Given

free reign, the medical profession shows itself to be open to

what amounts to butchery on a fairly wide scale, if sufficient

safeguards are not put in place.

1. The Current 1984 Surgeon General's Warnings Have Not Changed in Nearly 35 Years

In response to the Surgeon General's first major report on smoking and health in 1964, Congress passed the FCLAA to require warning labels on all cigarette packages. The text-only warning was written in small print and located on one of the side panels of each cigarette package. It stated “CAUTION: Cigarette Smoking May Be Hazardous to Your Health.” This language appeared on all cigarette packages sold from January 1, 1966, through October 31, 1970. In 1969, Congress passed the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act (Pub. L. 91-222), which slightly modified the warning statement on cigarette packages, but did not require any warnings in cigarette advertisements. The new warning language, “Warning: The Surgeon General Has Determined That Cigarette Smoking Is Dangerous to Health”, appeared on cigarette packages sold in the United States from November 1, 1970, through October 11, 1985. In 1972, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued consent orders requiring six major cigarette manufacturers and distributors to include in all of their cigarette advertisements a clear and conspicuous disclosure of the same warning required to be on packages (Ref. 35).

In 1981, the FTC issued a report to Congress that concluded that the cigarette health warnings had little effect on public awareness and attitudes toward smoking. The FTC report stated that the existing warning likely was ineffective because it: (1) Was overexposed and worn out; (2) lacked novelty; (3) was too abstract; and (4) lacked personal relevance (Ref. 52).

Subsequently, Congress again modified cigarette warnings by enacting the Comprehensive Smoking Education Act of 1984 (Pub. L. 98-474), which required the following four rotational health warnings on packages and advertisements:

Surgeon General's Warning: Smoking Causes Lung Cancer, Heart Disease, Emphysema, and May Complicate Pregnancy.

Surgeon General's Warning: Quitting Smoking Now Greatly Reduces Serious Risks to Your Health.

Surgeon General's Warning: Smoking by Pregnant Women May Result in Fetal Injury, Premature Birth and Low Birth Weight.

Surgeon General's Warning: Cigarette Smoke Contains Carbon Monoxide.

In addition, the law established the location and format for these warnings and mandated that they be rotated quarterly. Despite an FTC recommendation to change the size and shape of warnings, Congress retained the size and rectangular format of previous warnings (Ref. 218 at pp. 11, 12, 24, and 25; see also Ref. 52). As implemented, for example, this means the Surgeon General's warnings have continued to be printed in small type on one side panel of cigarette packages from October 12, 1985, to the present.

Nearly 35 years have passed since these changes and a substantial body of research shows that the current 1984 Surgeon General's warnings do not effectively promote greater public understanding of the negative health consequences of smoking and that there are better approaches to cigarette health warnings.

2. The Current 1984 Surgeon General's Warnings Do Not Effectively Inform the Public Because They Do Not Attract Attention, Are Not Remembered, and Do Not Prompt Thoughts About the Risks of Smoking

Pictorial cigarette warnings that increase message processing will aid consumer understanding of the negative health consequences of smoking. Cognitive theories and information processing models describe how information is gathered from the senses and is stored and processed in the brain (Ref. 111). Message processing is important to learning and understanding. Once an individual notices a warning, he or she mentally stores the information found in the warning and gives meaning to that information (Ref. 112). The individual mentally processes the information and builds on it, which helps them better recall and remember the information (Refs. 43 and 113). How much the information is mentally processed, reflected on, and thought about impacts how well the information is learned and understood (Ref.

114).

Attracting and maintaining attention is an important step in how communications, such as warning labels, can inform the public (Refs. 53 and 54). Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey (ITC-4) found that self-reports of noticing the health warnings on cigarette packages were positively associated with health knowledge among adults across the four countries studied, including the United States (Ref. 3). However, eye-tracking studies, which assess attention to visual stimuli, have documented low levels of attention to the current Surgeon General's warnings in both adults and adolescents, meaning that they do not attract attention (Refs. 55 and 56). One study of adolescents viewing tobacco advertisements found that the average viewing time of the Surgeon General's warnings amounted to only 8 percent of the total advertisement viewing time; nearly half (43.6 percent) of adolescents did not look at the warnings at all; and about one-third (36.7 percent) did not look at the warning long enough to read any of its words (Ref. 55). In that study, adolescents were unable to recall the content of the current Surgeon General's warnings or to correctly recognize the warnings from a list, indicating that the current warnings are likely ineffective among adolescents (Ref. 55). Similarly, a study of middle school students who viewed tobacco advertisements with the Surgeon General's warnings found the total amount of time spent focusing on the warning statement averaged slightly less than one second (Ref. 56). Similar evidence that the Surgeon General's warnings do not attract attention was found with a sample of adult smokers in 2011 who were instructed to look at a tobacco advertisement with a warning for 30 seconds, and of that time participants spent an average of only 2.8 seconds looking at the Surgeon General's warning specifically (Ref. 57).

As discussed in the following paragraphs, researchers have also found that the current 1984 Surgeon General's warnings are largely unnoticed and unconsidered by both smokers and nonsmokers. This is in accord with the findings of a major report on tobacco policy in the United States by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in 2007, which stated that the 1984 warnings on U.S. cigarette packages are both “unnoticed and stale” (Ref. 2 at p. 291). Similar conclusions were drawn in a study with a nationally representative sample of middle and high school students in the United States in 2012. Less than half (46.9 percent) of students who saw a cigarette package with the Surgeon General's warning reported seeing the warning “most of the time” or “always” (Ref. 58).

Noticeability of the Surgeon General's warnings is also low for adults. Findings from the ITC-4 published in 2007 found that only 30 percent of U.S. adult smokers noticed the warning “often” or “very often” (Ref. 4). Even if people notice the warnings, less than 20 percent of smokers in the United States report reading the warning text “often” or “very often” (Ref. 4). Moreover, additional findings from the ITC-4 found that less than half (46.7 percent) of U.S. respondents considered cigarette packages as a source of information on the negative health effects of smoking compared to 84.3 percent of respondents in Canada, where pictorial health warnings are required (Ref. 3). A study in 2009 found that 60 percent of U.S. adult smokers said they “never” or “rarely” noticed warnings labels on cigarette packages in the past month (Ref. 59). More recently, an analysis of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study, an ongoing, nationally representative, longitudinal cohort study of adults and youth in the United States, found that the current health warnings on cigarette packages often go unnoticed (Refs. 60 and 61). In the most recent publicly available data (data collected from late 2016 through the end of 2017), nearly three-quarters (73.5 percent) of the U.S. population, including both youth and adults, indicated they “never” or “rarely” noticed the health warnings on cigarette packages in the past 30 days (Ref. 61) (data available at https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NAHDAP/studies/36231). Among U.S. youth and adults who have noticed cigarette health warnings in the past 30 days, 52.0 percent of youth and 53.5 percent of adults responded that they “never” or “rarely” read or looked closely at the warnings in the past 30 days (i.e., do not attract attention) (Ref. 61).

Other data support that adolescents also do not see or read, and do not remember, the current 1984 Surgeon General's warnings on cigarette packages and advertisements. A study of ninth-grade students found that nearly one-third (27.8 percent) reported never seeing warning labels on cigarettes and nearly half (46.1 percent) could not correctly identify the location of the warnings on the package (Ref. 62).Similar data suggest

that people also failed to notice or read the current 1984 Surgeon General's warnings prior to the 1999 Master Settlement Agreement, when cigarette advertising was common on outdoor billboards. One study of adults found that drivers could read the entire warning message on only 5 percent of highway billboard advertisements and were only able to fully read the health warning on 18 of the 39 street billboards examined in the study (Ref. 63). All these results indicate that the current warnings are not appropriately conspicuous in advertisements compared to the rest of the advertising message, as discussed in more detail

below.

Not only

do the current Surgeon General's warnings not attract attention, but they also are not remembered—and remembering is a key component to long-term understanding of the information beyond surface-level noticing of the information presented. Viewing time of U.S. cigarette warnings is positively associated with recall (Refs. 55 and 56). Studies have documented low recall of warning statements for both adults and adolescents. In a study conducted with 13- to 17-year-olds who viewed five tobacco advertisements containing Surgeon General's warnings, only 19 percent were able to recall the general theme of the warning statement (Ref. 55). In another study, only between 20 and 53 percent of high school students could correctly recall each of the four Surgeon General's warnings even when they were provided with the actual wording, and some incorrectly recalled having seen a warning that was not being used at the time (Ref. 62). Similarly, low levels of recall were found in a study with high school students who viewed tobacco advertisements containing Surgeon General's warnings. Although most students (79 percent) reported seeing a warning, very few (15 percent) reported the warning statement's concept and even fewer (6 percent) correctly reported its exact message (Ref. 64).Beyond

being noticed and being remembered, additional measures of how well a message helps people understand its contents are to ask whether the message makes them think about the message's substantive information—showing an even deeper understanding of the information being communicated. These measures, often termed “cognitive elaboration,” are well-validated and often used in studies of cigarette health warnings (See, e.g., Refs. 80 and 84). Research demonstrates that the current 1984 Surgeon General's warnings do not prompt thoughts about the risks of smoking, and they are also perceived to be ineffective at making people think about those risks. Less than 40 percent of U.S. adult smokers in the ITC-4 reported that the Surgeon General's warnings make them think about the health risk of smoking, a level that was consistent between 2002 and 2005 (Ref. 4). In a study in Buffalo, NY, 62 percent of adult smokers reported that the Surgeon General's warning labels made them think “a little” or “not at all” about the health risks of smoking (Ref. 59). Participants in a randomized clinical trial with smokers in California and North Carolina reported that the Surgeon General's warnings made them think about the warning message only a little (an average of 2.3 on a scale of 1 to 5) and made them think about the harms of smoking only somewhat (an average of 2.9 on a scale of 1 to 5) (Ref. 65). That study also found that the Surgeon General's warnings were perceived as not impactful (Ref.

65).

Health communication research has found that adolescents also report that the current 1984 U.S. cigarette warnings do not prompt thoughts about the health risks of smoking. Among a nationally representative sample of U.S. middle and high school students who reported seeing a cigarette package, less than one-third (30.4 percent) reported that cigarette warning labels made them think about health risks “a lot” (Ref. 58). This proportion is even lower for adolescent current smokers, as only 13.8 percent reported that warnings made them think “a lot” about health risks (Ref. 58).

3. There Remain Significant Gaps in Public Understanding About the Negative Health Consequences of Cigarette

Smoking

Consmers suffer from a pervasive lack of knowledge about and understanding of the negative health consequences of smoking. A nationally representative survey of 1,046 adult smokers found widespread misperceptions regarding cigarettes and the negative health effects of smoking (Refs. 36 and 37). Thirty-three percent of adult smokers in the sample did not know that cigarettes were a proven cause of cancer (Refs. 36 and 37). Additionally, a quarter of the sample did not know that smoking was still dangerous to health even without inhaling (Refs. 36 and 37). Another study of 776 adult and adolescent smokers and nonsmokers asked participants what illnesses are caused by smoking (Ref. 15). Whereas the majority of respondents identified lung cancer as a smoking-related lung disease, only half mentioned emphysema (Ref. 15). A much smaller proportion identified cardiovascular disease (Ref. 15). Very few (3 to 7 percent) named any other smoking-related cancer (besides lung, mouth, throat, or gum cancer), such as pancreatic, cervical, bladder, or kidney cancer (Ref. 15). Very few mentioned negative cardiovascular effects, such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, aneurisms, or stroke, as smoking-related illnesses. In addition, people underestimated the percent of people diagnosed with lung cancer who would die from the condition (Ref. 15). Findings from another study indicate that approximately one-third of U.S. adult smokers believe that cigarettes have not been proven to cause cancer (Ref.

211).

Many

studies show that the public has limited understanding of other smoking-related health consequences such as impotence (Refs. 3, 12, 13, and 67; U.S. studies); stroke (Refs. 15 and 67; U.S. studies); gangrene (Ref. 12; U.S. study); vision impairment/blindness (Refs. 11, 119, and 201; non-U.S. studies); emphysema and chronic bronchitis (Ref. 11; non-U.S. study); other cancers outside of lung cancer, such as bladder cancer (Refs. 11, 13, 15, and 67; both U.S. and non-U.S. studies); the effects of secondhand smoke on nonsmoker adults and children (Ref. 16; non-U.S. study); and impacts on reproductive health and pregnancy (Refs. 13 and 67; U.S. studies). Studies in the United States have also documented that people are largely unaware of the health risks of smoking specific to women, including infertility (Refs. 13, 14, and 67), osteoporosis, early menopause, spontaneous abortion, ectopic pregnancy, and cervical cancer (Ref. 14 and 67). Research findings also show gaps in public understanding of the negative health effects of smoking during pregnancy. For example, one focus group study conducted in four U.S. cities with current smoking women ages 18 to 30 years found that participants had low to moderate awareness of smoking outcomes related to pregnancy (Ref. 68). These findings suggest that the public does not understand the complete range of illnesses caused by smoking, indicating gaps in public understanding of the negative health consequences of smoking.

B. Cigarette Health Warnings That Are Noticeable, Lead to Learning, and Increase Knowledge Will Promote Public Understanding About the Negative Health Consequences of Smoking

To understand a message, individuals must first attend to the message (i.e., notice and be made aware of the message), and then they must process the information in the message (i.e., acquire knowledge of and learn that information) (Ref. 70). When introduced in other countries, pictorial cigarette warnings have been shown to increase understanding of the negative health consequences of smoking (Refs. 3, 4, 39, and 48). The following section describes studies that demonstrate how pictorial cigarette warnings promote greater public understanding about the health consequences of smoking as they: (1) Increase the noticeability of the warning's messages; (2) increase knowledge and learning of the negative health consequences of smoking; and (3) benefit subpopulations that have disparities in knowledge about the negative health consequences of smoking. These studies incorporate measures that evaluate the impact of tobacco health warnings on understanding, many of which were drawn from the WHO's International Agency for Research on Cancer handbook on the methods for evaluating tobacco control policies (Ref. 71).

1. Cigarette Health Warnings That Are Noticeable Will Lead to Increased Attention to the Warning Message

To promote understanding of the content of a warning message, individuals must first notice the warning and must be made aware of the information contained in that warning (Refs. 53 and 54). In the scientific literature on consumer warnings, features that increase the noticeability of the warning label (also known as vivid features, such as images) increase the likelihood that people will see and pay attention to the warning message (Refs. 73 and 74). Physical features (e.g., use of pictures or color) that make a message more noticeable increase attraction and attention to the message (Ref. 75). A meta-analysis found that warnings, not specific to cigarette warnings, that include such features were more likely to attract attention than warnings without these features (Ref. 76). One experiment among a sample of U.S. adult smokers and middle school students found that participants who viewed pictorial cigarette warnings with full color spent more time looking at the warning compared to participants who either viewed black and white pictorial warnings or text-only warnings (Ref. 77).

Communication theory and research explain the message characteristics that impact how an individual is exposed to, attends to, comprehends, and understands the content of the message (Refs. 43, 78, and 79). Messaging that includes vivid features (e.g., images) increases attention to as well as cognitive elaboration (or thinking about) and processing of the message, which leads to increased message comprehension (Ref. 80). Messages that include vivid features, such as images, are easier to imagine and are more engaging compared to messages that do not include vivid features. An online experiment with 2,156 adults that examined varying levels and combinations of vivid features (i.e., testimonial images, identifying information, nontestimonial explanatory statements, testimonial explanatory statements, and contextual information) found that increasing the number of vivid features of cigarette warnings increased engagement with the message (Ref. 81).

a. Pictorial cigarette warnings increase attention to warning messages, which leads to increased understanding of the negative health consequences of smoking.

Research supports the role of pictorial cigarette warnings in increasing attention to and noticeability of warnings about the harms of smoking. More noticeable pictorial cigarette warnings are more effective in communicating the harms of smoking compared to text-only cigarette warnings in other countries as well as in experimental studies conducted in the United States (Refs. 3, 49, 50, 82, and 83). Pictorial cigarette warnings result in higher noticeability of and attention to the warning message compared to text-only cigarette warnings (Refs. 4, 48, 72, 77, 82-94). One study using data from ITC-Canada and ITC-Mexico assessed smokers' reactions to cigarette health warnings (Ref. 48). During the study period, Mexico had text-only cigarette warnings while Canada had pictorial cigarette warnings. Compared to adult smokers in Mexico, Canadian adult smokers reported greater levels of noticing the warning label and thinking about the harms of smoking. Another ITC study assessed noticing warnings in a sample of Chinese and Malaysian adult smokers (Ref. 83). After introduction of the new Malaysian pictorial cigarette warnings in 2009, there was a significant increase in the percentage of smokers who reported noticing the health warnings often or very often (54.4 percent pre-implementation compared to 67 percent post-implementation) (Ref. 83). Another study in the United States surveyed a sample of adolescents who had a parent, guardian, or other household member who participated in a randomized controlled trial in which a single pictorial or text-only warning was displayed on the parent's cigarette package for 4 weeks (Ref. 94). The pictorial cigarette warnings drew greater attention among adolescents in the study, and adolescents more accurately recalled the pictorial cigarette warning. In addition, the pictorial cigarette warning was recognized from a list of warnings more than the text-only cigarette warning.

Studies demonstrate that increasing notice of and attention to the information in a cigarette health warning promotes understanding of the message. Data from the ITC-4 showed that noticing health warnings on cigarette packages was associated with increased knowledge about the health consequences of smoking (Ref. 3). Smokers who reported noticing the cigarette health warnings were more likely to report believing that smoking causes the specific health consequences contained in the warnings, compared to those who did not notice the warnings.

Once individuals notice and attend to the warning, they are able to store and process the information in the warning that can be recalled later; these processes contribute to engagement with the message and lead to understanding. The important role of attention in message storing and processing is well supported by research (see, e.g., Ref. 54). For example, a study with smokers found that the frequency of noticing a cigarette health warning was associated with frequency of thinking about the dangers of smoking (Ref. 95). In addition, studies conducted in the United States with youth and adults have shown that longer time spent looking at a cigarette health warning was associated with greater recall of the information found on the warning (Refs. 56, 57, and 217), indicating that attention to a cigarette health warning leads to storing of the warning content and later recall of that

information.

b.

Pictorial cigarette warnings increase the likelihood that consumers will read, recall, and understand the warnings.

Research supports the role of pictorial cigarette warnings in increasing reading of and closely looking at the message warning as well as aiding comprehension and understanding of the information contained in the message warning. In a United States-based experimental study, repeated viewing of warning labels is associated with increased recognition and memory of the content of the label (Ref. 96). Research on recorded eye movement during reading of a warning label provides support for the link between reading and comprehension of the warning (Ref. 97). Measures of viewing duration (e.g., how long the eyes are fixed on specific words in the warning) are associated with how much participants are processing and can later recall that information (Refs. 56, 97, and 98).

Many studies support the finding that cigarette health warnings with vivid features (e.g., images) are read and looked at more closely compared to those without these features (Refs. 83, 86, 92; non-U.S. studies). One study of U.S. adult smokers showed that viewing a pictorial cigarette warning led to higher reported reading or looking closely at the warning, label memory and recall, and perceived label credibility compared to text-only cigarette warnings (Ref. 85). Another study of U.S. adult smokers showed that participants who had a pictorial cigarette warning put on their packs reported looking at the label more often and correctly recalled the label's contents more often than those with packs that had a text-only warning on them (Ref. 99). A study in Australia found that students reported more frequent reading and attending to the pictorial cigarette warnings after they were introduced, as compared to when text-only warnings were displayed (Ref. 100).

2. Pictorial Cigarette Warnings Can Address Gaps in Public Understanding About the Negative Health Consequences of Smoking

a. Pictorial cigarette warnings increase knowledge and accurate health beliefs by addressing gaps in public understanding about the negative health consequences of smoking.

Pictorial cigarette warnings increase consumer knowledge of the harmful effects of smoking, which promotes greater public understanding of the negative health consequences of smoking. Numerous non-U.S. studies support the role of pictorial cigarette warnings in promoting knowledge gains in cigarette-related health risks after implementation of those warnings (Refs. 3, 39, 48, 49, 100, 102-107, 202, and 203). One review examined health warning messages on tobacco products and concluded that health warnings increased correct knowledge about the negative health effects caused by smoking (Ref. 39). That review concluded that pictorial cigarette warnings are significantly more likely to draw attention, result in greater processing, and improve memory of the health warning (Ref. 39). Summarizing these effects among smokers, the National Cancer Institute concluded in its Tobacco Control Monograph 21 that large pictorial health warnings on tobacco packages are effective in increasing smokers' knowledge (Ref. 66).

Visual depictions of smoking-related disease in pictorial cigarette warnings help address gaps in public understanding of the negative health consequences of smoking by providing new information beyond what is in the text of the warnings through reinforcing and helping to depict and explain the health effect described in the text (Ref. 101; see also Ref. 39 at p. 330). Many studies have shown that exposure to pictorial cigarette warnings promotes knowledge of the negative health effects of smoking (Refs. 3, 48, and 102-107). For example, a study using data from ITC-Canada and ITC-Mexico assessed smokers' reactions to cigarette health warnings (Ref. 48). During the study period, Mexico had text-only cigarette warnings while Canada had pictorial cigarette warnings. Compared to smokers in Mexico, Canadian smokers had higher levels of knowledge about smoking-related health outcomes, such as stroke, impotence, and mouth cancer. Another study using ITC-4 data showed that Canadian smokers were almost three times more likely than non-Canadian smokers to accurately believe that smoking causes impotence; during the time of the study, Canada was the only country to require pictorial cigarette warnings and the only country that had a warning about impotence (Ref. 3). Another study surveyed adult male smokers to assess changes in awareness of health risks from smoking after Malaysia implemented new pictorial cigarette warnings (Ref. 102). Findings showed that knowledge of health risks across 13 different health conditions was greater after pictorial cigarette warnings were introduced in Malaysia (Ref. 102). In March 2007, Australia became the first country to implement pictorial cigarette warning on cigarette packages with the message that smoking causes blindness. ITC data from adult smokers were analyzed assessing knowledge that smoking causes blindness (Ref. 103). Findings indicated that Australian smokers were significantly more likely to report that smoking causes blindness compared to smokers in countries where there were no cigarette health warnings about blindness (Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States) (Ref. 103). After the introduction of the blindness warning, Australian smokers were dramatically more likely than before to report knowing that smoking causes blindness (62 compared to 49 percent) (Ref. 103). Another study assessing smokers' beliefs about the health effects of smoking in South Australian smokers found that, post-implementation of pictorial cigarette warnings, participants reported more health beliefs about smoking-related negative health effects, such as blindness/eye damage, stroke, harm to unborn babies, mouth cancer, throat cancer, blocked arteries, as compared to their health beliefs when previous text-only warnings were required (Ref. 105).

Research supports that exposure to pictorial cigarette warnings leads to knowledge gains about the harms of smoking among adolescents, whereas, as discussed earlier, the current 1984 Surgeon General's warnings do not. A report of Canadian warnings indicated that pictorial cigarette warnings improved knowledge of specific negative health effects of smoking among adolescents (e.g., increased knowledge of bladder cancer, impotence in men, mouth cancer, gum or mouth disease, reduced growth in babies during pregnancy, and strokes) (Ref. 108). One study that surveyed Australian students in grades 8 through 12 found increases in the proportion of students who recognized the smoking-related effects of mouth cancer and peripheral vascular disease after the introduction of new pictorial cigarette warnings on those topics (Ref. 100). Another study examined the effects of viewing health warnings on beliefs about the specific negative health effects of smoking among adult smokers and adolescents (aged 16 to 18 years). For both adults and adolescents, exposure to pictorial cigarette warnings that highlighted specific health topics led to increases in correct beliefs about smoking causing the specific health topic in the warning. For some topics (e.g., smoking causes strokes, smoking causes impotence), increases in correct health beliefs were only found in adolescents and not adults (Ref. 106).

There are a small number of recent studies conducted in the United States that failed to find an effect of pictorial cigarette warnings on increasing health beliefs about the negative effects of smoking (Refs. 77, 84, 109, and 110). The failure in those studies to find an association between exposure to pictorial cigarette warnings and increased health beliefs may be partly or fully attributable to the fact that, as previously described, the public already has a high pre-existing level of knowledge of the specific health consequences described in the warnings tested in those studies, some of which included warning statements set forth by Congress in the Tobacco Control Act. For example, a few studies have found increases in knowledge only of less-known conditions (e.g., blindness) but not of more well-known negative health effects (e.g., lung cancer) (Refs. 12 and 105). Notably, the increases in health beliefs from pictorial warnings were greatest for negative health effects that started with lower levels of prior beliefs about that health condition, such as gangrene and stroke (Ref. 12). This suggests that the impact of cigarette warnings on knowledge is greatest for topics that are not well known to the public.

In summary, pictorial cigarette warnings that convey the risk of specific negative health effects from smoking can increase beliefs and knowledge about the health consequences of smoking, particularly for negative health effects that are less known.

b. Pictorial cigarette warnings increase information processing and learning of new information about the negative health consequences of smoking.

Pictorial cigarette warnings that increase message processing will aid consumer understanding of the negative health consequences of smoking. Cognitive theories and information processing models describe how information is gathered from the senses and is stored and processed in the brain (Ref. 111). Message processing is important to learning and understanding. Once an individual notices a warning, he or she mentally stores the information found in the warning and gives meaning to that information (Ref. 112). The individual mentally processes the information and builds on it, which helps them better recall and remember the information (Refs. 43 and 113). How much the information is mentally processed, reflected on, and thought about impacts how well the information is learned and understood (Ref. 114). Health warnings are therefore frequently assessed by looking to how noticeable they are; how well remembered their content is; and how much they prompt individuals to think about their content.i.